- Interview by Brandi Katherine Herrera November 21, 2017

- Photography by Julia Robbs

Gail Bichler

- designer

- design director

Gail Bichler’s tenure at the New York Times has seen her through a number of roles; from designer, to art director, to her current post as the Design Director of the New York Times Magazine. Here, she reflects on the creative path that led her there, including her early beginnings in fine art, and choosing what she loved to do, even if that was a job. She shares why working in a team is far more satisfying to her than working as a team of one, and the importance of taking risks in concept and form, even if they sometimes don’t work out.

I’d love to talk about your creative path, and how that eventually led to your current role at the New York Times Magazine. Did any of your interests or experiences in young adulthood initially set you off in that direction? Art was an interest of mine as far back as I can remember. My parents were social workers, but they were also pretty creative in their free time. My mom liked to paint, and my dad made a lot of photographs, so I grew up with that kind of creativity in the family. I started taking art classes from an early age and continued them all the way through high school—both at school, and at the Cleveland Art Institute.

There was a period of time when my parents got divorced that I became absorbed in art, and it was nice to be able to settle into something I loved that I was also good at. I received a lot of positive attention for it in high school, and that was really good for me.

Drawing was your primary medium? It definitely was my main artistic pursuit. When I was younger, I used to draw a lot of cartoons, and I would also do these photorealistic drawings where I would take images from magazines and cut them in half and then try to replicate the other side. In high school, I also did a lot of traditional drawing exercises like figure drawing.

Then you went on to study fine art in college. What prompted your eventual shift to design? I paid for my own college education, so even in high school I worked really hard. I started working in restaurants when I was 14. In college, I waited tables at night, and during the summers I often had a lunchtime table-waiting job and a different dinnertime table-waiting job. By the time I had graduated, I had been waiting tables for about eight years.

I was really involved in fine art when I was in college, but I also realized that I was going to have to support myself. I just didn’t feel that I could do that by waiting tables as I tried to build my career in art. So I decided midway through college that I wanted my primary job to somehow be visual, while also still trying to pursue fine art. That was actually when I started to take graphic design classes, and it’s what sold me on the idea that I could do something visual that would also pay my bills. When I left college, I pursued a job where I could design art books, so that I could still be close to fine art and continue to be involved in that world somehow.

Financial viability is such a huge concern for so many artists and creative people. Were you able to continue a fine art practice while building your career as a designer? I was. While I was in Chicago working at studio blue, I was going into the print lab on weekends and making prints. But my graphic design job was ambitious; they were pushing really hard to do new and interesting things. It was a huge time commitment, so it ended up being pretty hard for me to do both.

You have to make a certain amount of art in order to get something good—a lot of really bad stuff, to eventually get to the good stuff. That’s been my experience. So when I was going into the print lab, I was finding that I didn’t have enough time to get past all of the mistakes or experiments to a place where I felt really good about what I was making. It was frustrating because I was stretching myself too thin. At the same time, I was starting to really enjoy graphic design. I ended up feeling like I was going to have to pick either that or fine art. I don’t think everybody has to pick, but when I pursue things, I pursue them wholeheartedly. I wanted to be able to put a lot of effort into what I was doing, and to make sure that I did one of those things really well.

“I was really involved in fine art when I was in college, but I also realized that I was going to have to support myself. I started to take graphic design classes, and it’s what sold me on the idea that I could do something visual that would also pay my bills.”

I really respect that ability to pursue a path with such intention and commitment. So, you chose design. Yes, I ended up loving design, so I picked that. My training in college was mostly in fine art, so I did a lot of learning at my first job in terms of typography, the craft of design, and the way to think about design and conceptualize things. All of that really drew me in, but particularly typography. And I also found that I could use a lot of what I learned from fine art in graphic design—elements of composition and color use, and a lot of other related ideas. When I found my job at the New York Times, I realized there was a way for me to work with artists, and to also be involved in making great conceptual art in the way that I do now.

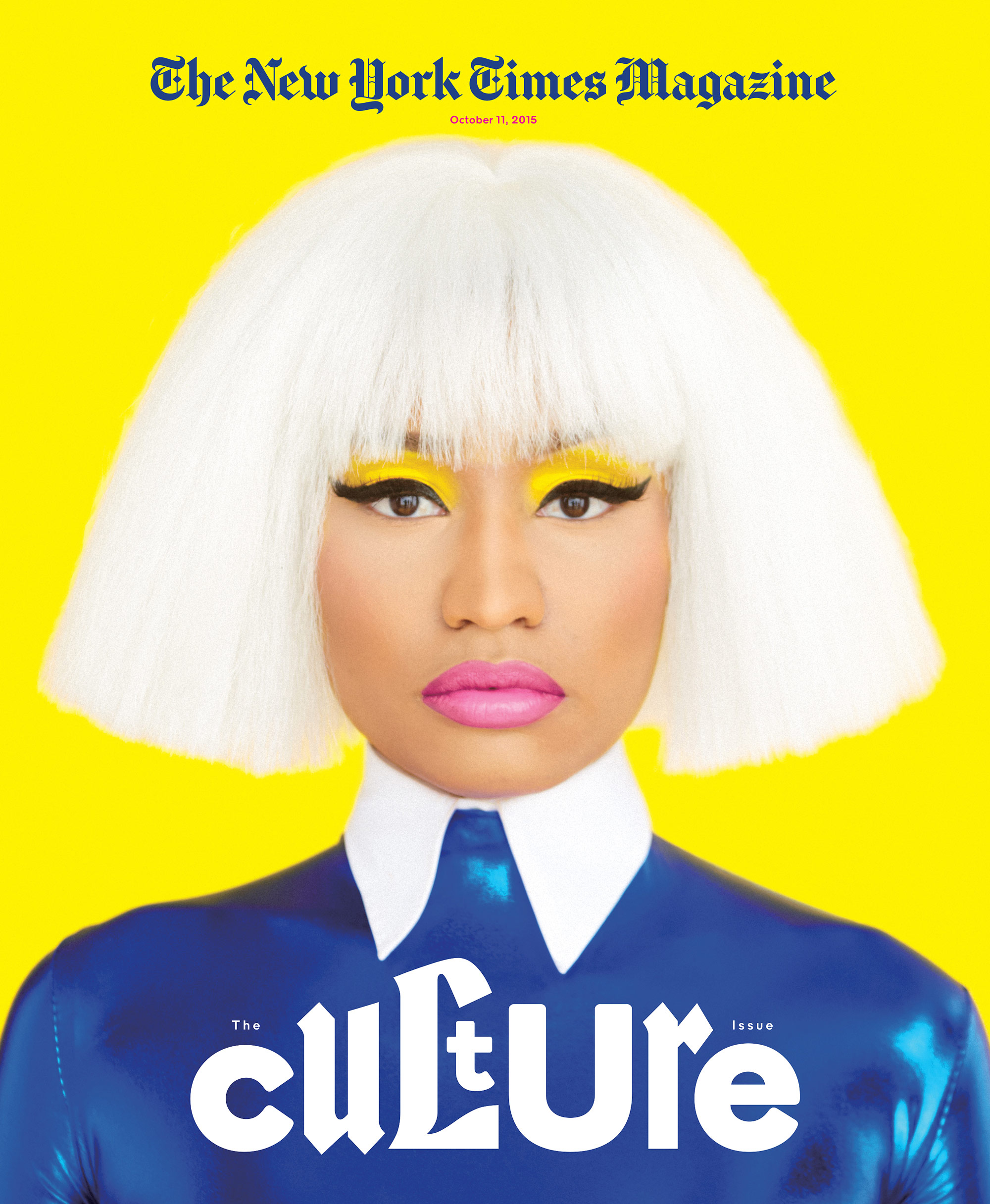

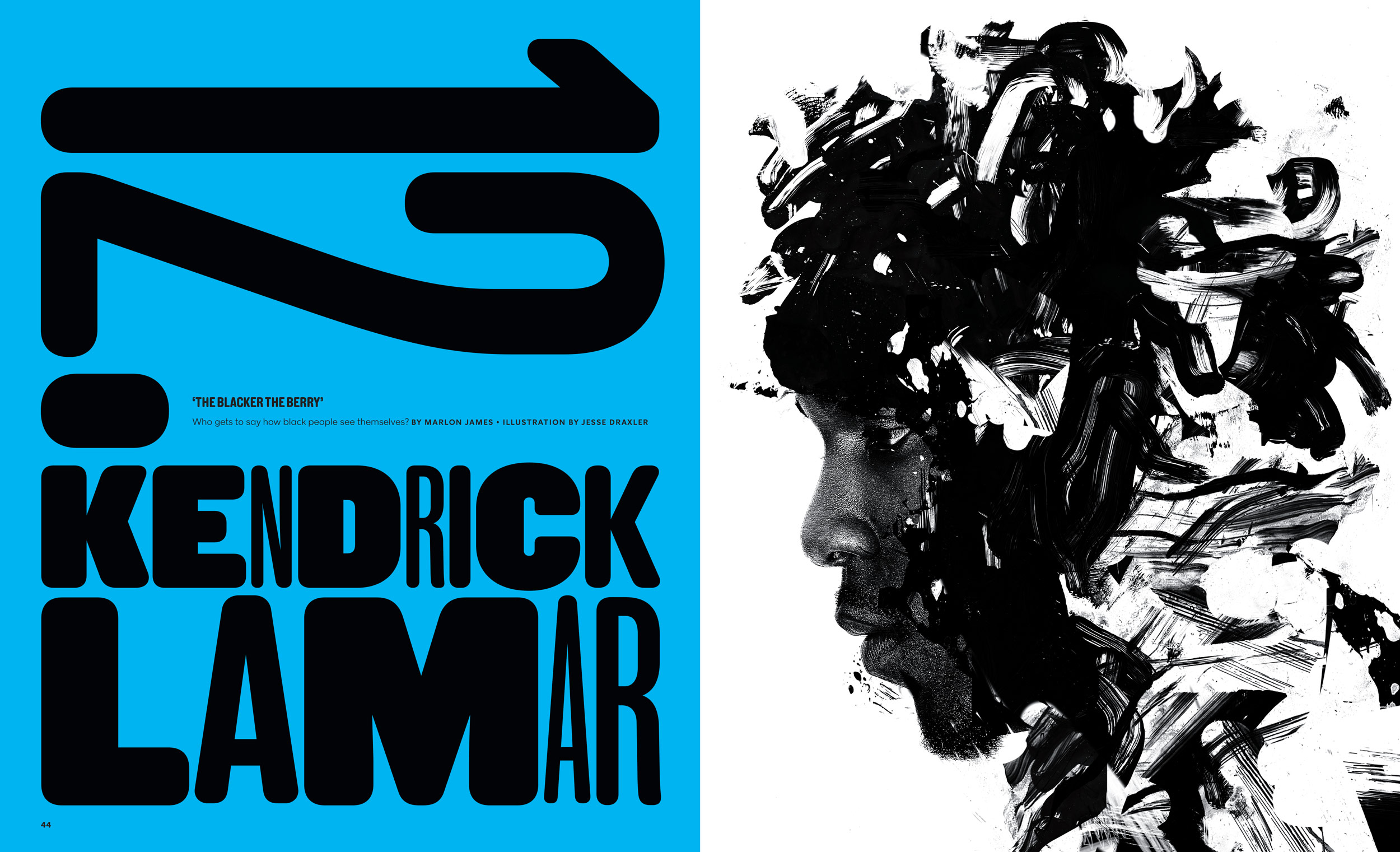

Let’s talk about typography for a moment. Bespoke type and typographic treatments have played such a large role in shaping the magazine’s visual language since its redesign. Was your own penchant for type the driving force behind that? I love type! (laughing) I’ve always drifted towards design that works with language in a certain way, but I think that was part of the brand before I joined the Times. The magazine has always been designed a bit differently from other mainstream magazines. It’s a little more stripped down and subtle, with more white space, and fewer devices. That approach always attracted me, and it reminded me of the kind of publication design that I did at the studios I worked for.

As far as the direction of the magazine now, I think it reflects my love of typography, but also our incredible staff. Matt Willey, our art director, is an amazing designer who makes his own typography, which we often use in our special issues. And a lot of the other people here also really enjoy making their own fonts. One of the great things about working in a group versus making something yourself is being able to draw on the talents of the people that you work with, and the talents here are not only considerable, they tend towards typography. It’s just a good fit, both in how I approach things, and how the people that I work with think about design.

It sounds like an incredible team. How has working and collaborating with them been different from the days when you worked as a freelance team of one? I started off executing as everybody does, making a lot of stuff to try to figure things out. And I always loved that kind of hands-on making of things. I had a good first experience with that at studio blue where I had a lot of guidance. Then I moved from Chicago to Minneapolis, where I opened my own studio, which I think was somewhat of a mistake. Although it did allow me to learn that I don’t like to work by myself. (laughing)

It can be so isolating to feel disconnected from the larger creative community. I was very isolated for a while. I wanted to continue making books for publishers and museums, and to do other kinds of cultural work, but I think it was a pretty hard move to make because I really didn’t know anyone when I arrived. So not only did I not have a business partner, I didn’t really have that many friends either.

Had there been someone I trusted to run things by, I think the work that I made would have been better. And I also think I would have been happier! (laughing) It’s pretty hard to make things in a vacuum. Just having that one other perspective can be really helpful. When I moved to New York, I knew that I didn’t want to start my own business—I wanted to be part of a team—and I was lucky enough to get that opportunity at the Times. I started as a designer at T, and then moved over to the Sunday magazine and worked my way up to the position that I’m in now.

And it sounds like you really enjoy your current role. I really enjoy being a part of a team here at the magazine. I love being around the other designers; giving input and getting input from them. But I have also loved being involved in the edit process, and working with Kathy Ryan, our incredible photo director, and her great team. There’s a real richness to the experience here, because there are so many people who are so good at what they do, and care deeply about what we make.

We have a lot of conversations—because people come at things with very different viewpoints—and everyone is passionate. Sometimes we’re all on the same page, and sometimes there’s a heated discussion about something. When I don’t get my way, I may be disappointed in that moment, but I usually realize later that there’s a reason for that, because the process here works. There’s been very few times I’ve come away from something having had some distance from it, and looked at it and thought we should have gone the other direction.

There’s a real feeling of discovery that can happen in seeing how someone else’s perspective and ideas can play out successfully, even if they’re totally different from what you initially thought might be successful. Our editor, Jake Silverstein, is very visual. At points he’ll tell me, “You know, I don’t think this is quite working.” And I’ll be disappointed, and think you know, I think it is working! But then I’ll come back to it and we’ll make something as a team that’s definitely better. I can’t tell you the number of times that’s happened.

Speaking of making, how has it been to shift from mostly executing creative to directing it, and what have you learned about yourself as a designer throughout that process? I worked under Arem Duplessis, a really talented design director at the magazine, for close to 10 years. He was a great manager, and I had the opportunity to watch and learn from him while I was both making a ton of design, and also managing. In our field, 10 years is a long stint in one place, (laughing) but I really enjoyed working with Arem, and enjoyed him as a person. And I also loved the mission of the Times so I allowed myself to stay in the spot that I was enjoying, while picking up and learning as much as I could.

Because I’ve worked here for so long, moving into more of a directorial role wasn’t actually such a hard transition. Taking a step up and thinking about the magazine in a more holistic, conceptual, and big-picture way was a welcome change. And I really enjoy being a director. That said, I also make sure that I still design things because I don’t ever want to lose that entirely. I often make the covers, or I’ll occasionally make a layout. I never have the time to make a full special issue on my own, but I also get a lot of enjoyment from working with the people on my staff on the features or issues that they’re making.

“When I found my job at the New York Times, I realized there was a way for me to work with artists, and to also be involved in making great conceptual art in the way that I do now.”

You’re both a mentor and collaborator. Yes. Matt, the magazine’s art director is very talented and experienced and the back and forth between us is a collaboration that I enjoy. With the younger designers in our group, I try to see what they’re making that’s good, and then find a way to push it further or suggest modifications, rather than taking over and making things mine. I actively try not to do that, because having all of these different voices and strengths in the mix—particularly for a publication that has as much varied content as we do—is important. I think that’s another thing you learn as you become a director. If you’re doing that well, you’re better able to motivate people to have the authorship over the things that they’re making.

It’s also great to watch people grow. Our deputy art director, Ben Grandgenett, came here as an intern and has been here four and a half years. When I watch what he makes now, I feel a real sense of pride. He obviously came with a huge amount of raw talent, but I’ve loved seeing how he’s developed over the years in working on our content. The last special issue he made was just so good. Watching him grow is something I find very rewarding.

I can imagine how rewarding it would be to work with someone like that from the very beginning. I have always loved working with younger people. Even back in the days when I was working in studios, I was often the person who mentored the intern. I like to teach! And I love it when a younger designer in our office wants to learn.

Did you learn any aspects of your approach to direction while working for Arem? I definitely learned a lot from him. He was open to the talents of the people around him, and he looked out for them in a way that has influenced me. Most designers think that the next step after hands-on designing is to be a director. And I don’t think that’s always the right step for everyone.

I’m so glad you said that. You are? (laughing)

I am! (laughing) I think it’s so true. And you’re right—most people working in creative fields don’t necessarily consider that management isn’t for everyone. Being a good manager is not a given at all. I think it’s something that you have to be interested in, and really paying attention to. And in many respects, it’s only something you can focus on once you’ve spent a lot of time focusing on the craft of what you make first, because it requires a huge amount of attention and thought. It can be hard when we’re making things that take up so much energy themselves.

Whether or not you’d be happy managing, and whether or not you would even be good at it, are definitely things to consider. A lot of people get into creative fields to make stuff because that’s what makes them happy. I’m not sure that everyone understands that in order to have the kind of space you need for the vision that’s expected as you move further up, you can’t actually make that much stuff. Otherwise, you’re in the weeds dealing with the details, and can’t clear the space you need to get to the bigger picture.

I learned a lot about management from Arem. He encouraged me to have my own vision, and to come at things from my own perspective. In some ways, I feel like he believed in me more than I ever believed in myself. He would consider any idea that I had just as much as an idea that he had, and would sometimes choose one of my ideas instead of his own. That gave me a lot of confidence.

“Most designers think that the next step after hands-on designing is to be a director. And I don’t think that’s always the right step…being a good manager is not a given at all.”

We’ve all experienced that moment at one point or another when our idea was chosen by a mentor—it’s such a thrill. Yes, it is! When somebody you really respect and think is great at their job—and I had a lot of respect for him—thinks your idea is good, it’s exhilarating. You think, oh, I could be good at this! (laughing) It’s a great feeling.

There’s a whole other aspect of the job that I do, which is all about considering the people you work with and trying to make sure they have what they need and are happy. It’s something I actively work on, and hope that I only continue to get better at.

That’s such great advice for someone who may have just started managing a team for the first time. Do you have any other advice for designers who aspire to follow a similar path as yours? My philosophy has always been to work as hard as I can. Design is a craft, and it’s something that you improve at the more that you do it. The same is true with conceptualizing art—coming up with visual solutions for content that’s not particularly visual—which is a big part of my job. That’s something I got better at as I went along, and I think it’s important for younger people to recognize that these are things you can develop. You have to start off with some kind of basic abilities, but the more you work at it, the better you get. It’s pretty easy when you’re young to look at somebody who’s been in the business for a long time and to think that they’ve just always been like that. But I didn’t start off having the skills that I have now; it took a lot of practice to get to this point.

So true. You think, how will I ever get there? It seems impossible. To be honest, even as I moved from my job as the art director of the magazine to taking over the design director position, I was truly scared. (laughing) If you’re not doing the job well, everyone is going to know—it’s a weekly magazine, and it’s very much in the public eye. There’s no hiding.

I watched both Arem and Janet Froelich, who was the director of the magazine before him, do it so well. You don’t want to be the person to come in and not do it well! There’s a certain amount of risk that you take as you assume new roles, and it can be scary. But that subsides. You grow into a role, and even if you don’t know that when you take it on, you have to proceed.

I told myself either I will be able to do this job, or I won’t! And that’s valuable information, too, you know? It was my way of easing my own fears about it. It’s funny, because I had conversations with Arem as I got the job, and he was clear with me that he very much thought I could do it. But you still have your own self-doubt and worry, and you have to just jump in and take the risk anyway.

Do you ever feel that beginner’s anxiety in producing each new issue, knowing the great responsibility you have with such a highly visible publication? I always have worries about how things are going to turn out, and there have been periods of time where I’ve had to push myself to take greater risks. Pursuing riskier ideas and visuals is the way that you make something good. And doing that on the kinds of timelines I work within, means that there’s always the possibility that the thing that I’m working on might not work out and I might have to publish it anyway. Or, I might have to come up with a last-minute save.

These things are all part of my daily work routine. A lot of things are last minute, and yet I want to be as ambitious as I can be, as does everyone I work with. I often remind myself that because we make so many issues per year, there are going to be highs and lows and some level of variance. If you’re making something that’s consistently pretty good, but you don’t have anything great, that means you’re not pushing yourself or taking enough risks—you’re just making sure nothing fails. And I think if you’re pushing to make new and interesting things, there are going to be times when that thing that you tried doesn’t turn out the way you wanted it to.

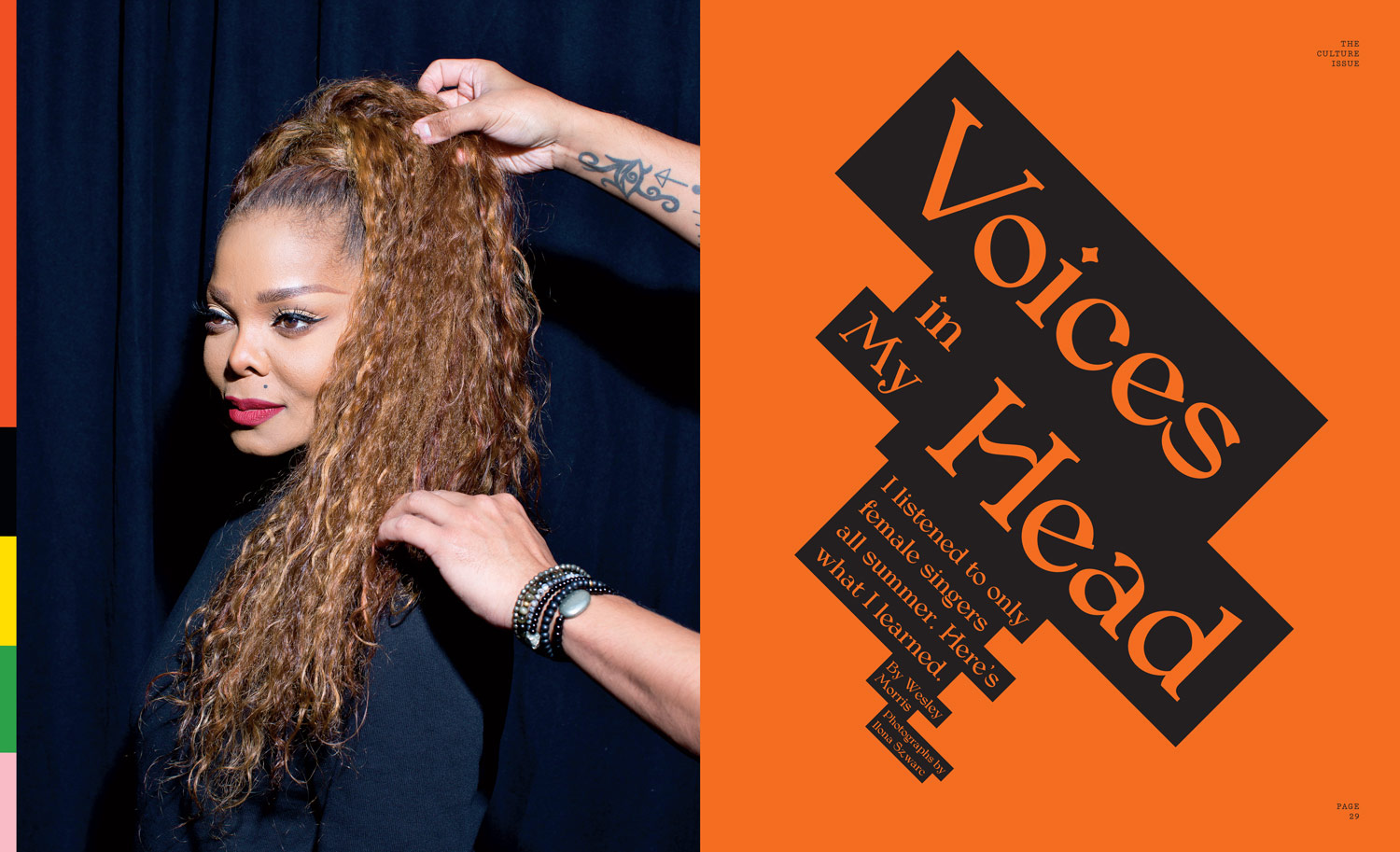

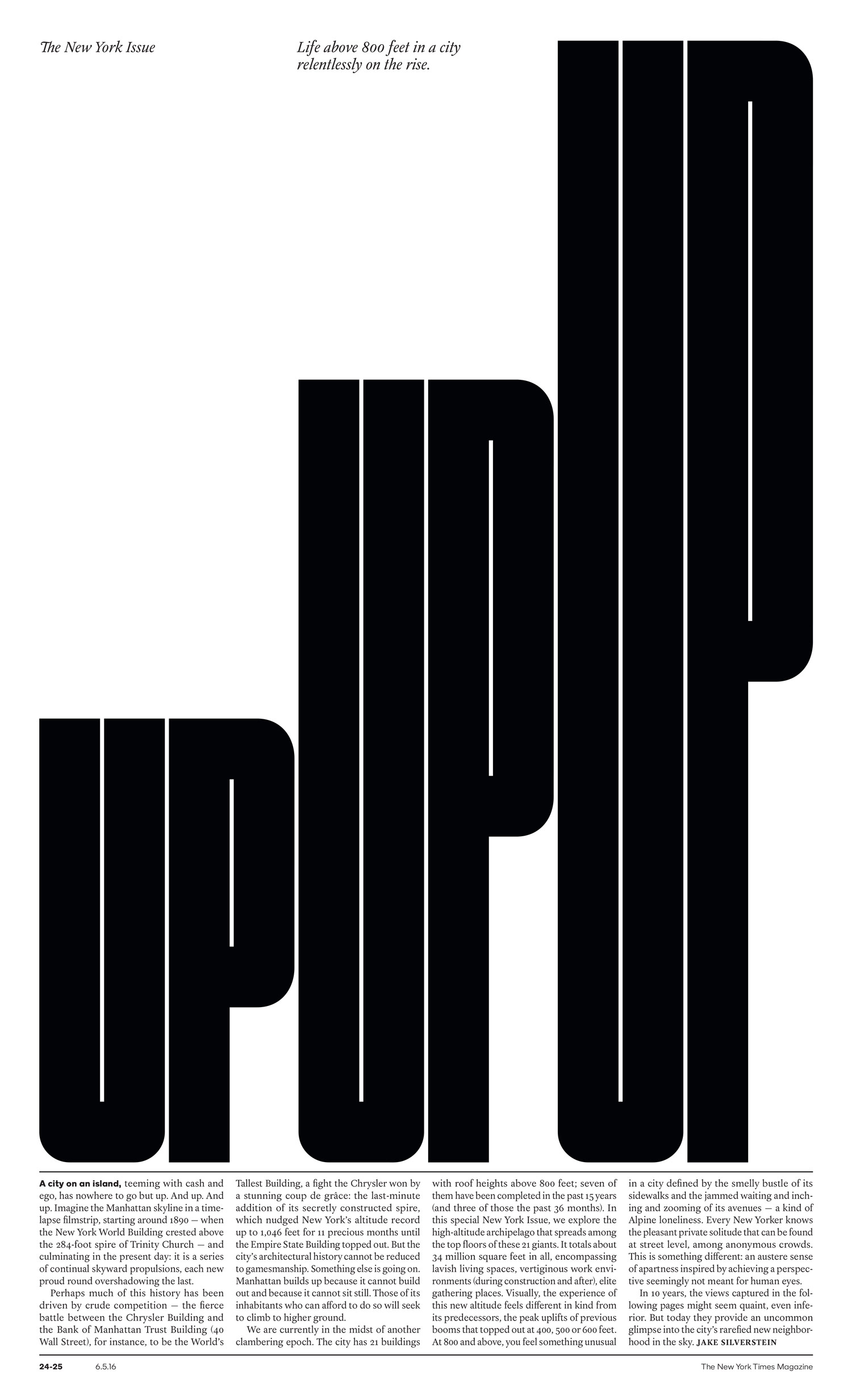

That makes so much sense—particularly with the special issues, which are conceptual and immersive. They’re more like an experience than a collection of stories where design is tying the overarching threads together. Are there specific issues you feel that you broke new ground with, or took greater risks in creating? The New York issue we did last year where we turned the entire issue on its side, was an idea that Matt came up with. We always do a New York-themed issue, and within that we usually pick sub-themes to make the issue more unique or interesting. So this one was about altitude, and things that were happening above 800 feet in New York.

We talked about ways we could make use of the physicality of the magazine in order to address height, and Matt had the idea to just flip the entire thing on its side, which I loved. We first mentioned it in a meeting with Jake and it definitely sparked his interest, but then he moved on from it. And we realized that if we were really dedicated to pushing that idea through, we were going to have to make a mock-up to show everyone what the potential was. So, we went and made a mock up! And when everyone eventually saw it, that was when they got on board.

“One of the great things about working in a group versus making something yourself is being able to draw on the talents of the people that you work with…”

I remember that issue so well. It was pretty amazing. Our photo team commissioned photography to fit that super vertical format. We redesigned everything, including the crossword puzzles and the front of book. Everything was oriented in the same direction, which we were adamant about making happen, because we felt like it would be a bad experience for people if they had to flip the magazine back at some point.

We knew we might take a lot of heat for doing something like that, so we only attempted it because we thought the idea was so clearly in sync with the content, and would really add something to the issue. It’s not as though our publication is aimed at designers that are totally good with us experimenting with the format—it’s for everyone. And not everyone wants to see that; it can be really disorienting. But if people look at it further and then come to understand why it was done, and if they think it’s smart, and makes sense, and actually adds to the experience in some way—then I think they warm up to it.

There was something great about that issue’s boldness, and how the format of the magazine influenced a design. Matt ended up drawing typography the height of an entire spread, which was the biggest type the magazine has ever published. And the visuals were completely driven by that decision. I was really proud of how it turned out.

With special issues like this, we’re trying to think of the magazine almost as a kind of container: how it can be used in a way that’s surprising in terms of what’s contained in it, how it’s structured, and its physicality. Like you said, we’re not necessarily trying to pull together five different stories that relate to a certain topic. We’re trying to think about how to tell stories in a way that varies much more than that. For one food issue we did, the concept came from a photographer, George Steinmetz, who was doing all of these great aerial photographs of big food. And when I say “big food,” I just mean the industrialized production of food. Although we did put a really big apple on the cover. (laughing)

Saying “big food” does immediately conjure up images of giant stacks of pancakes in the Guinness Book or something. (laughing) I know! It really does. (laughing) Well, George came to Kathy with this photo essay in mind. Jake, who really loved the photos, decided he was just going to make an entire issue using that as the theme. He really understands visuals. It’s entirely because of him that what we make looks like it does. He’s willing to take those risks, and to publish both challenging writing and visuals as well. He sees what that adds to the thing we make, and I’m so grateful for that.

So what we ended up doing for that food issue was a really nontraditional format, where all of the photography was from that one photo essay. Those images really became their own story. And we also commissioned a bunch of other stories that we snaked throughout the issue, and illustrated them so that the visuals for those stories were very different, but they were still interwoven in a really interesting way.

What kind of feedback has the magazine received in response to these kinds of experiments in concept and form? For the most part, the response has been pretty positive. There will always be people that are unhappy about this thing, or the other thing, but I think people are interested in being surprised, and (hopefully) also delighted. As long as it has meaning, and is well done, I think people are open to certain kinds of change.

Many of the special issues we’ve done, people have loved. But the New York issue, where we turned the whole magazine on its side, received pretty polarized responses. Many people loved it, and many people really didn’t. (laughing) I remember somebody tweeted, “Thanks a lot, NYT! Now my neck is sore.”

And it’s all your fault! (laughing) Matt and I were joking, Did they not know they could turn the magazine 90 degrees while they were reading it? (laughing) Another colleague told me that somebody had said to her that they were cranky when they initially got that issue. But as they started to look through it, they realized it was smart, and that it meant something, and then they came around to it in the way that I mentioned before.

When we take risks like that, we know not everyone is going to love it. The good thing is, if you don’t love this week’s issue, there’s always next week’s. That’s something we continually think and talk about. We can do this! Because we make 52 issues.

That’s so important to remember. Each new issue you make is not the last. Being that you’re allowed this level of experimentation and also work with such an incredible team, do you feel creatively satisfied? I do! I feel really creatively satisfied, and I love my job. I sometimes feel like such a cheerleader for this place, (laughing) but I wouldn’t have stayed here as long as I have if I didn’t love it and feel like it was such a privilege to be here.

I get to work with really smart people. And I get to make something that I’m invested in that I think is useful out in the world. Like you said, I get a huge amount of creative freedom, which I know isn’t the case for everyone. And I feel incredibly lucky for that.

“If you’re making something that’s consistently pretty good, but you don’t have anything great, that means you’re not pushing yourself or taking enough risks—you’re just making sure nothing fails.”

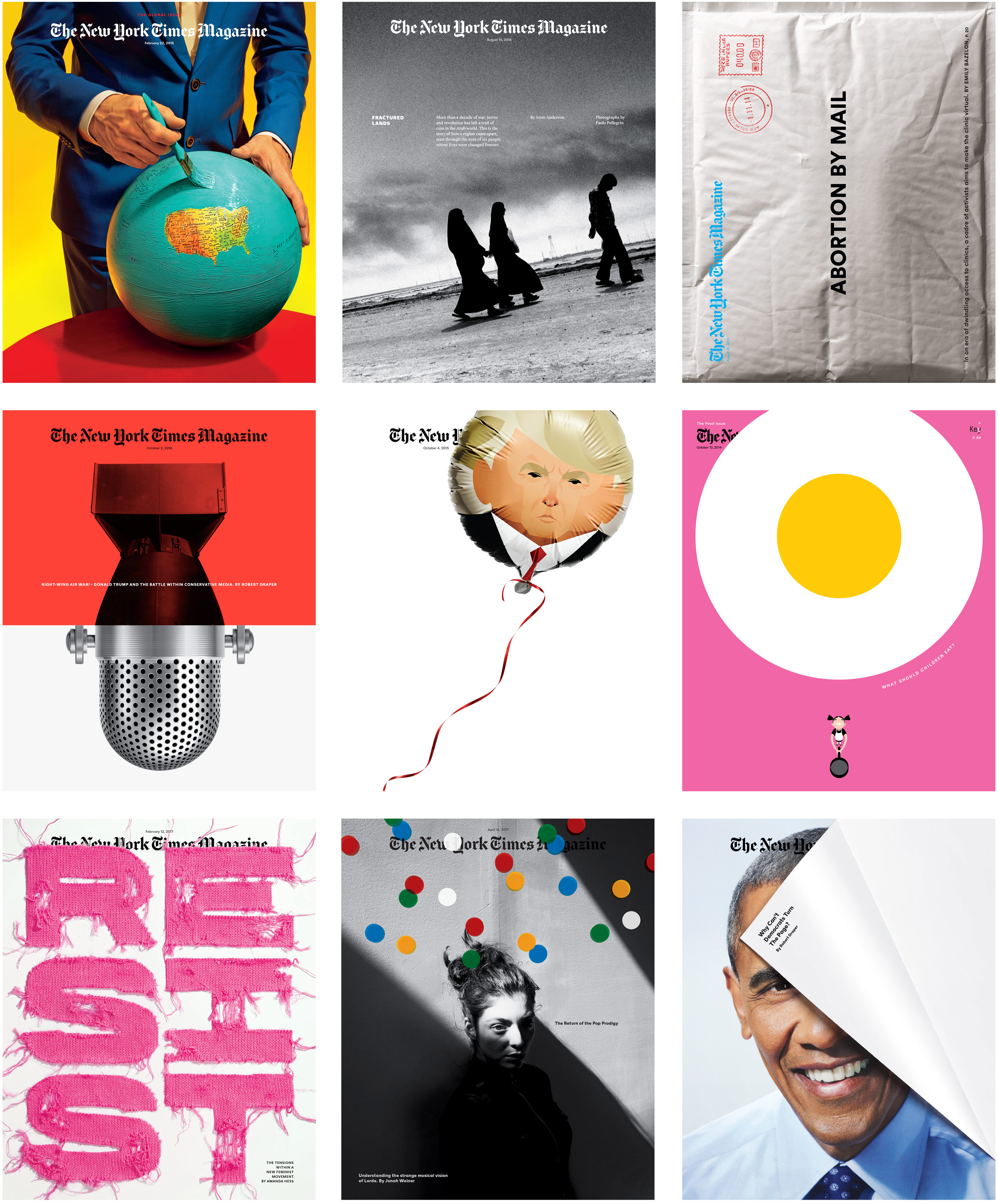

Credits for magazine cover grid

Global issue cover, photograph by Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari; Fractured Lands cover, photograph by Paolo Pellegrin; Abortion by Mail cover, photo illustration by Johnny Miller; Right-Wing Air War cover, photo illustration by Matt Dorfman; Trump Balloon cover, photograph by Jamie Chung and portrait illustration by Stanley Chow; Kids Food issue cover, illustration by Christoph Niemann; Resist cover, lettering by Sagmeister & Walsh; The Return of the Pop Prodigy cover, photograph by Jack Davison; Why Can’t democrats turn the page?, photo Illustration by Janie Chung, and Obama photograph by F Scott Schafer.