- Interview by Tina Essmaker November 1, 2016

- Photo by Dan Robinson

Nick Onken

- entrepreneur

- photographer

New York-based photographer and entrepreneur, Nick Onken, started out in design, but his path evolved as he pursued his interests, including photography and travel. Nick spoke with us about growing up in the suburbs of Seattle, the sacrifices he chose to make early on in order to build a career he loves today, and how we live into our possibility when we stop talking and start making.

Tell me about where you grew up and how you spent your early years. I spent my childhood Bothell, Seattle, which is in the suburbs about 20 minutes north of the city. I grew up in a very conservative Christian home and went to youth group throughout school, until I was about 21. Then I started to explore life outside of that.

As a kid, I drew and painted. I loved drawing Mickey Mouse and other Disney characters in middle school. In high school, I got into advanced placement art, so I had to create a portfolio. We were asked to explore different mediums to see what we enjoyed. I drew, painted, sculpted, and did photography within the program. I had taken a photography class in high school and worked in the darkroom, but it never registered as career material. It was just part of the program.

How did your childhood shape your beliefs about creativity or what was possible as a creative career path? Thankfully, my parents were always encouraging. My dad did Bob Ross paintings and was actually really good. He also did underwater photography for fun. He encouraged me to explore those things, which is why I was into art from a young age. I felt good about moving in that direction.

There was never pressure to go into a certain profession? Never. Funny enough, my parents were always more about me being happy with what I’m doing than making money. They were happy and wanted me to be happy, too. We weren’t necessarily poor, but I look at the world around me now, and it’s a completely different one that my parents never experienced. They didn’t know that world of making a lot of money or wanting me to live in that space. Looking back on it, I feel like that was why they took the stance of, “Do what you love, and we hope you can make enough money.”

Did your parents work more traditional jobs? Yes, my dad worked as a fuel injection mechanic and then got into production and managing vendors for products. My mom was—and still is—an elementary school secretary. And they were both part of our lives growing up, which I’m grateful for.

And you went to college after high school? Yes. I loved computers and tech, so the idea of combining art and tech was interesting to me. That’s why I went to school for graphic design. I went to Shoreline Community College, but I didn’t finish my four-year degree because I got a job.

One of my first jobs out of high school was working in the cleaning room of a laser manufacturer (laughing), which was a funny experience. Then I worked my way up to the marketing department to do a design internship. Granted, I didn’t have anyone to teach me, but they gave me a cubicle and access to design programs. That’s the thing with art. To be a successful artist, you have to do it yourself. School gave me a foundation, but I learned more on my job because I did it on my own and taught myself.

Did you decide to quit school because you were learning more on that job? Well, it took me three years to finish my two-year degree. I went down to part-time at school because I was working full-time. Then I got a job designing book covers for a self-publishing company based in the suburbs of Seattle. I did that for a year or two. Also, while I was in college, I sold Cutco knives.

I remember those. I’ve sat through a few demonstrations. That’s hilarious. Yeah, I sliced my fingers a few times.

So you were really hustling. Yeah, and the most painful part was having a regular job. That made me itch inside. I worked the book cover design job for a few years and then left to start freelancing as a designer.

I got a job that gave me enough money to travel for a month around Britain, which was an eye-opening experience. It was my first time overseas, and I loved it. It made me want to travel even more. Since then, I’ve been to over 70 countries.

“That’s the thing with art. To be a successful artist, you have to do it yourself. School gave me a foundation, but I learned more on my job because I did it on my own and taught myself.”

At what point did you get into photography and make the switch from design? I started freelancing in design at age 21. A few years later, in 2003, digital photography started to get good enough to use for print and I got a digital camera, a glorified point-and-shoot. I started to shoot stuff for my design work and put a photo gallery up on my design website. In the meantime, my friend had just returned from Africa where he built an IT network for a nonprofit. I wanted to travel and help people with my skills, but design wasn’t it. I asked myself, well, what about photography?

I decided to pitch a nonprofit design client of mine to split expenses for a trip to Africa so I could build a photo library for them. I literally had no clue what I was doing, but I wanted to travel. They said it sounded great, so I crafted a two-month trip to go to four countries in Africa: Zimbabwe, Uganda, Kenya, and Burundi.

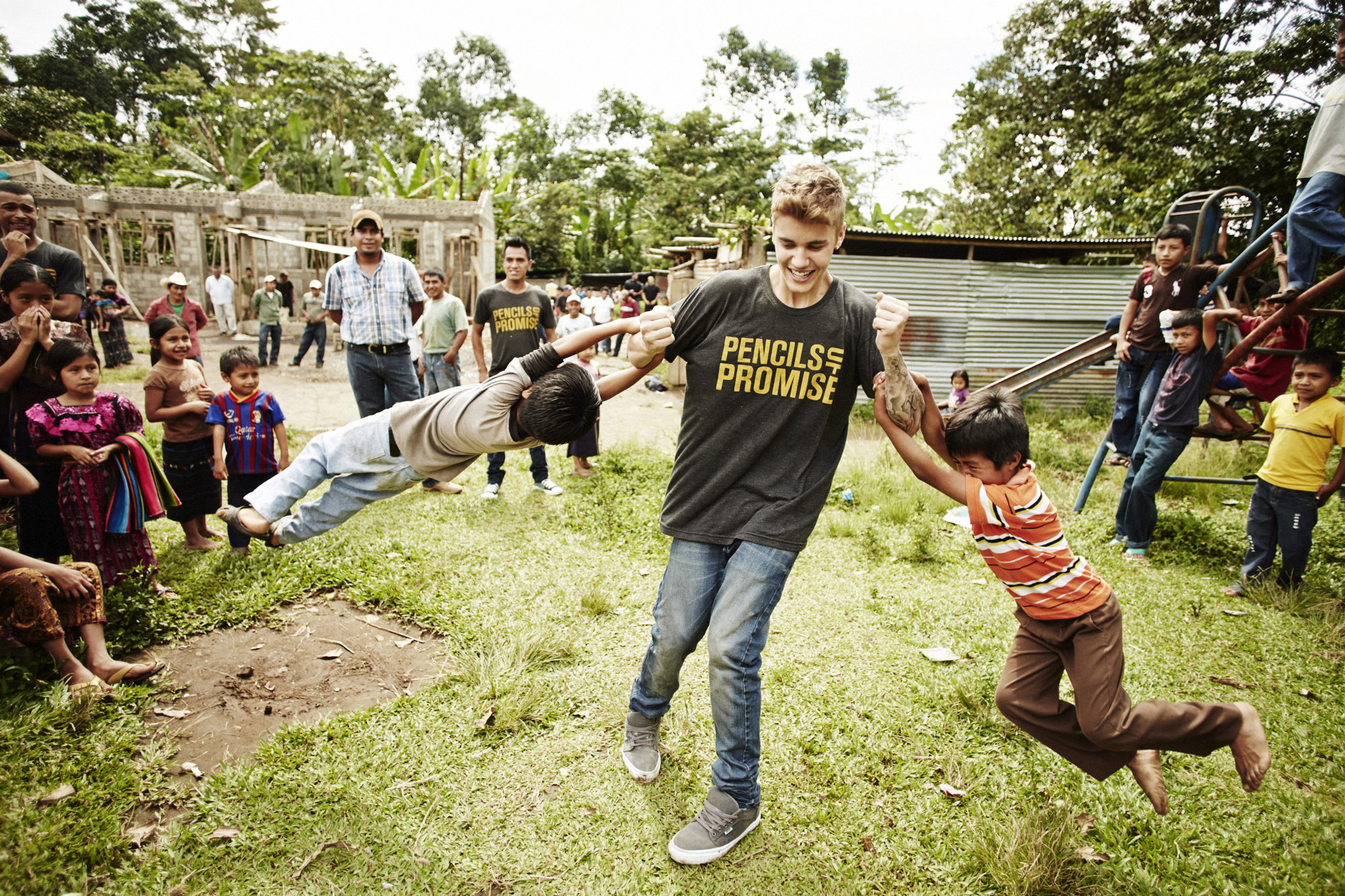

I think that trip shaped my life. It opened my eyes and gave me a little more empathy in my worldview. Since then, I’ve adopted a philosophy of giving and working with charities, which later led to working with Pencils of Promise, a nonprofit that builds schools in developing countries around the world.

When you returned from Africa, did you decide to focus more on photography? It took me six months to recover after that trip. I didn’t know how to live in a place where people were so ungrateful and negative. It’s easy to fall into that.

When I came back, I did website design for a photographer and then I started to bombard him with questions about cameras. That’s when I started to learn more. He shot products and weddings and invited me to come out on his lifestyle and portrait shoots. Then he hired me to periodically assist him. We became friends and he was a mentor to me. Then I started to shoot my friends and created a portfolio. Eventually, he told me, “You’re a good designer, but you have something for photography. I think you should be a photographer.”

That’s affirming to have someone who’s doing it for a living tell you that you’re good at it. Definitely. That’s when I made the jump. I went to school for design and I wanted to do it—I loved it. But at that point, I knew that if I was going to be a better designer, I would have had work at a studio to learn more. Then photography happened.

Once you made a decision to focus on photography, what were the first few years like? Were you still paying the bills with design work? What was great about it was that I had the flexibility to continue to design. I could design one day and photograph the next two. Plus I cut my expenses so I was living for $500 a month. My rent was $300, my car insurance was $150, and then I had my $50 cell phone bill. Whatever money I made from photography was put back into my business to buy gear. I do remember the meal-stretching days where I’d make a spaghetti dinner and see how many lunches I could get out of it.

You bring up a good point. One of the things that can’t be overstated is the importance of keeping your overhead low in the beginning. Absolutely. You have to trim off all the unnecessary things. Cutting your expenses is huge. If you really want to play the game, you have to make hard decisions. But if you do it right, you can become successful and make a living.

At what point did you move out of Seattle, and was that a big risk for you? Leaving Seattle was huge because it’s a small city, you know. The first move I made was to Paris for half a year. I didn’t know anyone initially, but I met some good friends there. I wanted to live abroad in a city that was photography-centric. I chose Paris and I’m glad I did. It’s a magical city.

I actually got my first big freelance job around the end of 2004 just before I moved to Paris. The job was for Nike and I got it through a friend who I had grown up with in church. He was an art director and had moved to New York and worked at RGA. Nike called me on a Monday to shoot all these pro sports players in San Diego, Pittsburgh, St Louis, and LA.

It was a shoot on location with studio lights, and they were also filming a commercial on site, so I had to set up my studio on the side so they could jump over to me after they were done filming the commercial. I had to scramble to rent gear in San Diego the day before Christmas Eve. Luckily, a friend who was a producer at Nordstrom introduced me to a friend in LA who had gear and was available to assist, so I hired him. We drove the gear down to San Diego, did the shoot, and I hired him to travel with me to the other cities as well.

That job was a success and I thought, “I made it! I’m shooting for Nike now.” But I didn’t see more work for the next two years. I took that money from Nike, moved to Paris for half a year, and realized I couldn’t build a career there. I moved back to the US, traveled for a few months, and moved to LA in 2006.

What were you doing to pay the bills during those two years that you didn’t get another commercial gig, and did you ever get discouraged and think you made the wrong choice? When you’re freelancing, you don’t know when that next check is coming. It’s scary. Luckily, I had enough design chops to get jobs while I worked on building my photography portfolio. It was challenging, but that money I got on the Nike job lasted me a year. It was less than a real year’s salary, but I was frugal and stretched it out. I picked up small design projects, which kept me afloat and I started to shoot weddings. That was a good experience because it taught me how to use natural light and use my camera on the fly.

How long did you live in LA before you moved to New York? I was in LA for three years. When I moved there, I started over again. I did whatever I could to pay the rent and invest in my business. It wasn’t until 2008 or 2009 that I started actually making money, which was five years into photography.

In 2007, more work began rolling in and I got another job for Nike. It was a twelve-day trip to Mexico City, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, and Rio. What’s funny is that I shot for a nonprofit in Asia in 2006 and that’s when I hit my stride with travel photography. I knew what I was looking for and I got better images, which helped me get that next Nike job.

You work with an agent now. Has that influenced the type or amount of work you get? Working with an agent catalyzed my career. In December 2008, I got my first ad campaign through an agency—it was for Secret deodorant. I was shooting some stuff for Cosmo in New York, too. The next year I started to make a little more money and thought about getting a bigger place in LA, but then I decided to move to New York in 2009.

“You have to trim off all the unnecessary things. Cutting your expenses is huge. If you really want to play the game, you have to make hard decisions. But if you do it right, you can become successful and make a living.”

How do you know when it’s time to get an agent, and has it paid off? To work in the big leagues, you kinda have to, unless you’re a really good business person. Even then, having an agent takes a portion of the business off of you. It separates the business from work.

I was already going on meetings on my own for years, showing my portfolio at ad agencies. An art buyer liked my work and I told her I was looking for a new agent. She introduced me to three, I interviewed five, and chose one in New York. Having an agent has given me the credibility to get big commercial gigs.

Now, there are a lot of smaller jobs—all the social media jobs. It’s easier to get in as a young photographer through those jobs, but when I was getting in, there was a huge gap. To get into the ad world with the big brands is a huge jump. It’s a whole different world.

You’ve been solely focused on photography since you’ve lived in New York, right? Yes, but I will say it has been changing the last couple of years, which started when I took an emotional intelligence leadership training a few years ago in LA. A friend of mine, Lewis Howes, who hosts The School of Greatness podcast, told me about the training and it shifted my perspective. There’s a whole set of limiting beliefs that we all have that we grew up with that keeps us from making the decisions we need to make in order to live into our possibility.

With the landscape of photography changing, my business had slowed down and I was having a hard time dealing with going through the highs of shooting campaigns to the industry being turned upside down with the market crashing. What do you do? As an artist, it’s hard to separate yourself from your art. Then you add commercial value on that. People stop hiring you as much and you wonder what’s wrong with you. It was a dark time for me.

I’d always had a blog focused around giving back to the photography community, which I called Shoptalk. I created that blog because I read Never Eat Alone by Keith Ferazzi, which is about making connections through adding value. After I did the emotional intelligence leadership training, I had a passion to share in a different way.

“It takes a lot to jump off a cliff and do your thing, especially in art because there’s a whole creative process and journey you have to go on before you can actually make money with your art. How do you pay the bills? How do you get your art to that place?”

Is that when you started your podcast? Yes, that training inspired me to do my podcast. I was fascinated with how people created, but also with the psychological side of it—what fears do people have? It takes a lot to jump off a cliff and do your thing, especially in art because there’s a whole creative process and journey you have to go on before you can actually make money with your art. How do you pay the bills? How do you get your art to that place? I’ve been fascinated with that across the board—not just with photography, but with music, design, acting. How do people get to where they are?

And that was Shoptalk Radio, which you just relaunched as Nion for your 100th episode. Tell me about the rebrand. I’m shifting the focus a little bit. Nion has been percolating over the last few years as I’ve thought about the kind of legacy I hope to create. The values that I’ve distilled over the past few years—being creative, giving back, making a living—have trickled down into my work.

Nion is the umbrella for my work and it’s about inspiring people to live life in color—a creative, fulfilled life. I want to create a brand and community around that for people to be a part of as they inspire each other to live that life. I’m still trying to decide where it’s going to go, but I want to create products, merchandise, and do collaborations with other designers.

Have you thought about what else you want to explore in the coming years? There’s a side of me that would love to take positive messaging and bring it into an art space to inspire people. I’m also thinking about how I can do a live audience podcast or paint public murals or paint on products. I feel like everything ties together through my perspective on life, which spills over into various mediums.

Yeah, what you start out doing isn’t the thing you’re going to do forever. It changes and evolves as you grow and learn and want to incorporate those things into your work. When we get stuck is when we become too regimented and continue to do things the way we’ve always done them. Exactly. I mean, I never thought I’d be a photographer. I thought I’d always be a graphic designer. I didn’t know anything about the world of photography or how to make money with it. You never know what will happen.

Am I going to be a photographer down the road? I have no idea. I still love it, but will it be commercially viable in a few years? It’s changing so quickly, especially with the way that digital media is affecting print. I can already see the industry decline in terms of rates because there are more photographers and less jobs. People are trying to figure out the social media landscape and don’t want to pay for it, so they’ll reach out to somebody who’s new. I don’t know where it’s going to go and I’m enjoying these other things that I’m interested in. The trick is to figure out where the money will be made while still doing what I love.

“…I never thought I’d be a photographer. I thought I’d always be a graphic designer. I didn’t know anything about the world of photography or how to make money with it. You never know what will happen.”

Anyone who’s trying to pursue a creative path—that’s what we’re all after. How can we make money to do the stuff we want to do and provide value to people? If you provide value, there’s often an exchange of money, but how can you do that without selling out? I think there’s a way to create a signature for yourself, no matter your art form—a signature that people seek you out for. I think that’s harder to do with photography nowadays because it’s been so diluted.

Yes, you do have to find a way to differentiate yourself. That becomes harder in a world that’s so connected. Everyone is in the game now. Yeah, it is much harder. We’ll see where things go. I don’t know where we’ll end up.

Me either, and that’s scary and fun and exciting. Yeah, I think you just have to approach it with the mindset of figuring it out as it evolves. When I interviewed Usher for my podcast, he said, “You evolve or you evaporate.” If you don’t evolve with your art and with the way culture is moving, you’ll evaporate.

I agree with that. So, you’ve traveled around the world to photograph people in developing nations and have shot celebrities, like Justin Bieber. What has photographing so many people taught you about the human spirit? We’re all the same. We all have emotions, whether we’re Justin Bieber or a kid in Africa. If you treat people on a human level across the board, that’s going to make a great space for humanity. That’s why I believe in education, especially emotional intelligence.

I was at an event last year and got to photograph the Dalai Lama and somebody asked him, “What do you think the world needs the most?” He answered, “Emotional hygiene.” If everyone could learn to take care of themselves emotionally on a daily basis, the world would be a much better place. People would take care of each other. I definitely believe in that philosophy.

Over the years, you’ve worked as a designer and photographer and started multiple side projects. What’s your advice to someone who’s on the precipice and wants to start something? Just do it and know why you want to do it. Is it about fame or the craft? You have to do it for the craft because if you don’t, you’ll never have what it takes to do the work or get through the hard times. You have to love what you do because you love it—not because you want to be onstage or be a rock star. Because you’re going to have to sacrifice so much to get to the place you want to be.

For sure. The hard times will come, and if you don’t love it, you won’t stick it out. Exactly. So I guess my advice is to just do it. People often talk about what they want to do, but not many actually go and do it. Those are the people who become successful.

“Is it about fame or the craft? You have to do it for the craft because if you don’t, you’ll never have what it takes to do the work or get through the hard times.”