- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker September 3, 2013

- Photo by Darrin Ballman

Over the Rhine

- musician

- songwriter

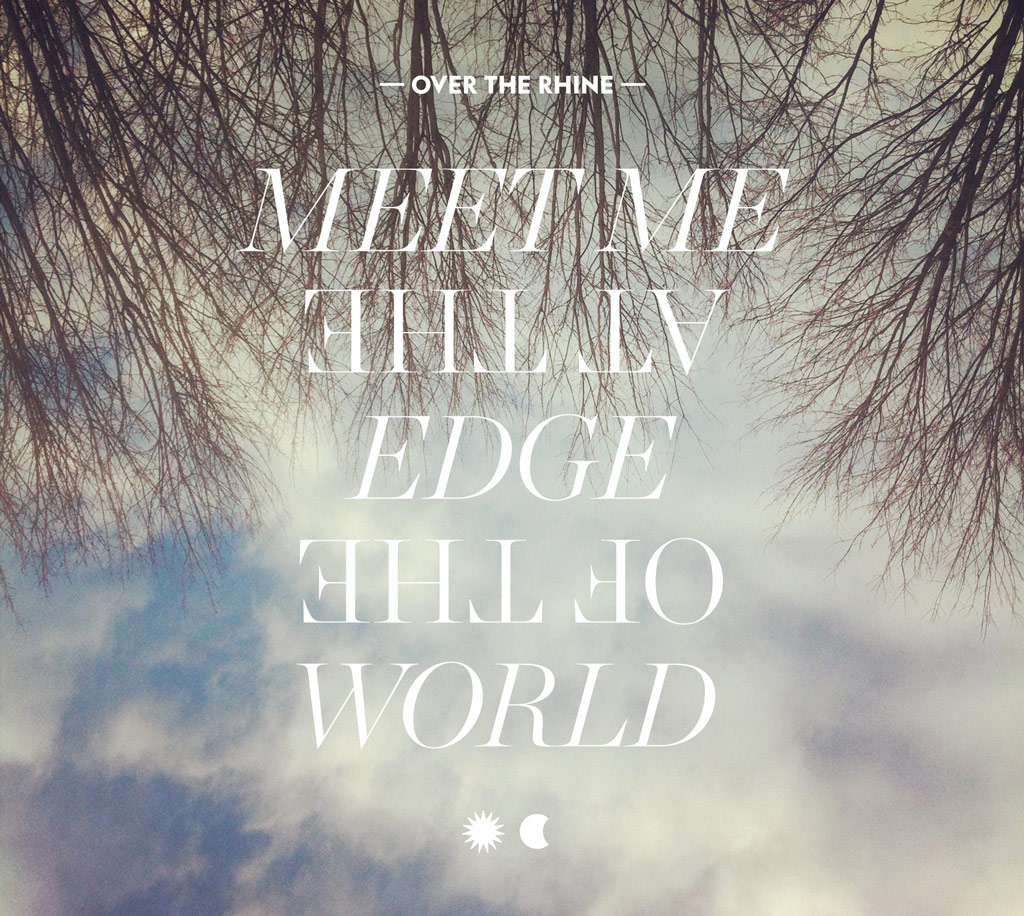

Over the Rhine has been touring and recording for over two decades. The husband and wife creative partnership of Linford Detweiler and Karin Bergquist has flourished into a songwriting team that has been included on various lists of “Greatest Living Songwriters.” Their newest project, Meet Me At The Edge Of The World, is a double album full of songs that revolve loosely around the farm in Southern Ohio that the band calls home.

Interview

Describe your paths to becoming musicians.

Linford: Both of my parents grew up on Amish farms where musical instruments were strictly forbidden. My father and his brother secretly hid a guitar in the haymow, and they would sneak out after dark to play it. One day, their other brother, not knowing what was buried in the hay, accidentally ran a pitchfork through it—that was the end of the guitar. My mother lived on a different Amish farm, and she had wanted a piano when she was a girl. One of her schoolteachers helped her cut out a cardboard keyboard and she would pretend to play it in her bedroom, which allowed her to make the music that was inside of her. The idea of music being dangerous is sort of in my family’s history.

When my dad was 21, he was offered the family farm. The only thing he knew for sure at the time was that he wasn’t a farmer, so he set out into the world and began exploring. He eventually met my mom, had six of us kids, and bought a record player with a bunch of different records. The new chapter from then on could pretty much be called: “Let the Music be Heard.” I was about seven years old when my father realized that I was interested in music. He opened up the classified ads one day and circled all of the pianos that were for sale. We went around town, played all of them, and he let me pick out the one I thought was right—we paid $10 for it. That piano is where I went as a child to figure out stuff that I didn’t have words for.

I have loved music ever since. I met Karin in college, and we decided to hang our hats on the songwriting peg. We’ve been writing, recording, and performing for over two decades now.

And what about your path, Karin?

Karin: When I was a little girl, I was asked that inevitable question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” From a very early age, I said I was going to be a singer. At the time, I didn’t know that I could sing, or that I’d ever be any good at it; I didn’t know much about music, but I loved the way it felt in my body. I always knew I would somehow get involved with music, and my gateway drug was singing. (laughing) I’ve never wanted to do anything else.

Like many children, I grew up in a broken home. My parents had gone through a bitter divorce, and my maternal grandmother had suffered from some traumatic life events, so I was exposed to a lot of emotional upheaval early on. I turned to music as a means of healing, and I inevitably became the family entertainer and comedian to lighten the load on my family.

Linford to Karin: That’s where your comic genius came from.

(all laughing)

Karin to Linford: Yeah, thanks for acknowledging that, babe—I was forced into the limelight just to change the weather of family discourse in the living room. (laughing)

My maternal grandmother’s second husband, Ray, was my first musical influence. He took me under his wing when I was a little girl, and we were best pals; whatever he did, I wanted to do. We had Hee Haw dates every week. (laughing) We’d sit curled up in front of the TV watching Roy Clark and Buck Owens, and—wow—what an education that was for me! Not only did I get to experience incredible music and quirky humor, but I got to have a wonderful association with music and laughing in a safe place. My step-grandfather also introduced me to gospel music, which was very important to me musically. I had asked him what God was, but he was an atheist, so he didn’t know what to tell me. One Sunday morning, he came downstairs in a suit and my grandmother said, “Where the hell are you going?” (laughing) He told her, “I’m taking Karin to church,” and that’s where I first heard gospel music. Sadly, he passed away not long after that. It was really hard for me to lose him, but I still take him with me through music.

Afterwards, my family moved to a really small coal-mining town in Ohio called Barnesville, where my grandmother’s family was based. It was a completely different culture; music had a different flavor there. My grandmother gave me the basic John W. Schaum piano lessons, but I kept looking for music wherever I could find it.

When I was in high school, my writing was encouraged by a great English teacher named Mr. Carissimi. He was very eccentric; some of the kids were scared of him because he was a little quirky, but I thought he was cool. He took my mom aside one day and told her that I was one of the best writers he’d had in 17 years. I wasn’t really thinking seriously about it at the time; I just enjoyed it. It took me several years to figure out what to do with writing. By the time I went to college to study music, I began to think that maybe I could put music and writing together. And that’s when I met Linford.

You two have been making music together for a long time. Can you tell us how you met and started performing together?

Linford: Karin and I met at a little Quaker liberal arts college in Northeast Ohio, where we were both studying music. That’s where we first had a chance to make music together, and it felt like there was a little chemical reaction whenever we played. A lot of people came up to us after performances and said, “Wow, what was that?” It felt like the room changed; we never forgot that feeling.

In Cincinnati, we found an old German neighborhood called “Over the Rhine.” We were small-town kids, so when we discovered that place, it felt as if someone lifted up a European city, flew it across the Atlantic ocean, and dropped it whole in Ohio. It was a magical, ragged, dangerous neighborhood—it was considered the bad part of town, but we felt drawn to it. We borrowed the name, did our early recordings there, and launched the band.

Back in the early 90s, it was all about trying to get signed to a major label. It was very exciting when we were contacted by I.R.S. Records—we were signed by the same A&R rep who signed R.E.M. We were with them for a few albums, but when they closed their doors in 1996, we were back on the streets starting over. At that point, we thought about packing it in and getting on with our lives.

Shortly after that, however, we put out a little collection of songs called Good Dog, Bad Dog, and that record opened a lot of doors for us. It ended up out-selling all of our I.R.S. releases combined. We learned that we didn’t need a major label to get our music into people’s hands, and we’ve never looked back. Sometimes we’ve done records with the help of a label, and other times we’ve just done our own thing. Since 2007, we’ve had our own label called Great Speckled Dog, named after our Great Dane, Elroy. (laughing)

It’s been an adventure. I always thought I’d eventually phone home with the bittersweet news that we were done with the band and were going to get “real” jobs. At some point, I realized I was never going to make that call: this is my real life.

“I always thought I’d eventually phone home with the bittersweet news that we were done with the band and were going to get ‘real’ jobs. At some point, I realized I was never going to make that call: this is my real life.” / Linford

Did you guys start dating when you first met, or did it develop after you started playing music together?

Karin: In college, I had a job in this old barn that served as the recreation center for the campus. I was in charge of passing out the billiard balls—really exciting work. (laughing) Linford would come in and play video games or ping pong—to Linford wait, what did you do there? I don’t remember. You tell it.

Linford: I thought, “What a lovely girl sitting behind the counter.” I went over and introduced myself, and Karin has absolutely no memory of that first meeting—that’s the kind of first impression I make on women. (laughing)

Karin: That’s terrible! (laughing)

Linford: We weren’t romantically entangled when we first started the band, but music is powerful and romantic, so we started dating a few years afterwards. We’ve been married for almost 17 years now and have lived to talk about it. (laughing)

Karin: I remember the first time I noticed him. He was playing a Ravel piece on the piano and something resonated in me; it really caught my attention. There were a lot of other students who played in recitals, but there was something about the way he approached it that caught my ear. I thought, “I want to know that person.”

Linford: Thank God for the piano! (laughing)

Karin: We had really good chemistry musically, but we had to figure that out before the romance happened. We were there for a reason: to make music. It’s not that there wasn’t an attraction there, but we wanted to see what the music was all about first. Realizing that we were attracted to each other was a bonus.

It’s a difficult thing to be with your partner all the time and still be productive and creative. We liken it to having two gardens: the first is the band, what we produce musically, and everything that goes on behind the curtain; the second is our marriage—we’ve learned that we have to take care of that in a separate way. Sometimes it’s really hard to take care of both, especially during times like this when we’re releasing a project. It takes all of your mental, emotional, and physical energy, so we have to work hard at it. It’s definitely worth it, but it’s not for the faint of heart.

Linford: Well said.

Tina: That’s an interesting perspective. Ryan and I are also a married couple who work together. What’s your best advice for a married couple whose work and personal lives are interwoven?

Linford: Ah, the ol’ entrepreneurial couple dilemma. (laughing)

Karin: I would tell you to fight naked.

(all laughing)

Karin: I’m kidding—but I’m also not kidding. It’s important to have the awareness that what you’re doing is challenging, and to have the right tools to care for both parts of who you are. Somebody asked Johnny Cash what the secret to a good relationship was and he said, “Separate sinks.” You need your space.

Linford: I think it’s important to have a realistic handle on the pros and cons of being romantically together and working together. Most importantly, you need to have a common dream that you’re sharing and working toward. I think a lot of couples look in from the outside and would love to have that kind of a connection to their partner, but the challenge is the fact that it never goes away. When you’re running a business together, the connection between your marriage and your work is always right there. You don’t leave it at the office—it’s something you carry with you.

A marriage-business partnership is an ongoing experiment: you never necessarily figure it out once and for all. But it’s a worthy enterprise to create something with your partner. We found a marriage counselor who has been a good ally. Sometimes we just need fresh words and someone to act as a sounding board for what’s happening. I would encourage any entrepreneurial couple to get a little outside help; somebody who can give you a fresh perspective.

Karin: Yeah, anytime you think you can do it yourself, it’s a little deceptive. It’s really important to allow other people to help you through life. The “me” mentality is kind of dangerous because we really can’t do it alone, and I think that’s why we fall flat on our faces sometimes. We need to be reminded that it’s okay to ask somebody, “How did you get through this?” or, “What kind of tools can you share with me so that I can move forward?” Helping others move forward a little bit is a really necessary part of life.

Linford: Sometimes artists think they get to play by a different set of rules than everybody else. Going back to the metaphor that Karin used: if you’re trying to grow a garden, it doesn’t really care whether you’re an artist or not. It still requires sun, water, and attention—you don’t get to skip steps just because you’re an artist.

Did either of you have an “aha” moment when you knew music was what you wanted to focus on?

Linford: When I first got out of college, I was hired as a side man with a band to do a little touring in New Zealand. We were supposed to play at a little festival in the mountains for about 400 people, but it was pouring rain. We had assumed the show had been cancelled, but the audience was very much of the opposite mindset. Whatever we had to give, they wanted to experience it. I played that set thinking, “There aren’t very many things in this life that people will stand in the rain for,” but apparently music is one of those things. When I got back home, I called Karin, and she and I and two other friends started the band shortly after that. I think that was a bit of an epiphany for me.

Karin: My “aha” moment happened at birth, so I’ll just leave it at that. (laughing) Some people come out swingin’, and I came out singin’.

Have either of you had any mentors along the way?

Karin: We’ve had a lot of mentors. Obviously, there have been musical mentors—singers and songwriters who have been incredibly inspirational—but we’ve also had mentors who are a little outside of the box. We have a friend, Michael Wilson, who is a photographer. He’s been a good friend and our families have been friends for years. Michael’s musical knowledge and vocabulary is expansive, and he’s introduced us to so much through his love of music and his eye and the photographs he makes, and who he is as a person.

We also have a dear friend named Barry Moser, who is an illustrator. He’s done hundreds of books and knows so many people. We connected through a series of workshops we teach in the summertime: he does life drawing and we do songwriting. We became good friends after we found out that we both love good martinis and big dogs. (laughing)

Linford: One of the great things Barry told us was, “Don’t call yourself an artist. Let other people decide whether your work is art or not, and call yourself by what you do.” If you write songs, call yourself a songwriter; if you paint pictures, call yourself a painter. It’s not really your concern if it’s art or not. It’s about getting the work done.

Karin: It takes the pressure off. Let other people figure the rest of that out and just focus on your craft.

“If I didn’t believe that songs were bigger than me, I would have picked something else…These songs are able to go out and connect with deep moments that people are living, struggling through, or celebrating.” / Linford

Was there a point when you two decided to take a big risk to move forward?

Linford: There have been countless risks, and we both have a very high tolerance for taking them. It started with telling people who cared about us that we were going to start a band. (laughing) How many parents dream that their kid will grow up and start a band? We didn’t know anything about what we were doing. We just knew that we were going to put everything into it, and if it didn’t work then we would be starting over, penniless on the street.

Karin: That’s why they went with the girl with good credit. (laughing)

Linford: We worked so hard to get signed to a major label and—

My gosh, Karin! I’m out here picking the cucumbers, and there are so many of them.

Karin: He’s in the garden now, so you’re getting a play-by-play of our farm. (laughing)

Linford: My gosh—there are dozens of cucumbers. Dozens!

(all laughing)

Karin: We had a few rough years when the cucumbers didn’t make it, but we have them this year. It’s really great. (laughing)

Linford: Holy moly. Anyway, we worked really hard to get signed with a major label, but when I.R.S. Records closed their doors in 1996, we were out on the streets. It was a big risk to proceed with a music career without a record label, and a lot of people expected us to relocate to Nashville or New York. Moving from the city and buying a ramshackle farm in the middle of Ohio—where we actually have some roots and history—was also risk. If you set out to do anything good, though, risk is part of the picture.

Did you two feel like crowd-funding the last few records was a risky thing to do?

Linford: We did initially because it was a very novel idea when we did it with The Long Surrender several years ago. We only knew of one or two other songwriters who had done it. Crowd-funding has since become very common, but it’s still risky to go to your audience and say, “We’d love to have some help for this next chapter.” We tried to make it fun, and the response has been extremely positive.

Karin: What was important for us was not wanting people to feel like they were giving us something for nothing. People want to feel like they’re a part of something, and how many people do you know who love music but can’t make it themselves? This gives them a chance to be a part of the process. Again, it’s that communal thing that makes you realize you’re not in it alone.

We wanted to give people something special in exchange for their financial support, so we did something that we’d never done before. For our second fan-funded album, one of the pledge levels let backers attend a concert here on our farm. We knew it was going to be risky because we weren’t sure how it was going to go or if anybody would care, but it ended up being amazing. It blew up, and we had about 500 people come both nights we played.

It felt a little scary to look out at my back yard and see all these people I didn’t know! (laughing) But everybody was so cool. Our audience is unique, because they’re really great people who are in tune with a lot of the things that matter to us. There wasn’t a scrap of trash to be found after we had all those people here—it was like nothing had happened! They were so respectful. Everybody had a good time and we’ll probably do it again.

“It’s an exercise in growth to be thankful for what you’re given every day.…We live in a culture where we’re taught to be entitled, and it’s a shame because you don’t have very many learning moments when you’re entitled.” / Karin

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Linford: My family was certainly skeptical in the early days. We also have chosen family and have never really had to explain ourselves to the people who are close to us. Somehow they get it and have been extremely supportive.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourselves?

Linford: If I didn’t believe that songs were bigger than me, I would have picked something else. Karin mentioned that we both have a history of growing up in various churches and so forth. One of the scriptures that has haunted me from my past is the one that talks about offering someone a drink if they’re thirsty, food if they’re hungry, or clothing if they’re naked. There’s so much need in the world—a lot of times it’s overwhelming. Who knows where to start? The great thing about offering someone songs is that they get passed around. They show up in prisons, hospitals, bedrooms, dorm rooms, or on a soldier’s iPhone in Iraq. These songs are able to go out and connect with deep moments that people are living, struggling through, or celebrating. That connection is what keeps us coming back; we’re blessed to be able to make a living.

I was struck by something I saw the other day. Joni Mitchell, who is turning 70 was being interviewed and was asked what she was most proud of in her career. She thought about it, and said it was when she heard from a couple of teenage girls who said they sat in their bedroom and played her records after their mother had died. Joni Mitchell is one of the iconic songwriters of our generation, with an incredible career full of experiences, but what really mattered at the end of the day was how her music connected with other people in those big moments.

Are you satisfied creatively?

Linford: I don’t think we’re ever completely satisfied. There’s a restlessness—somebody referred to it once as “divine discontent”—that is part of any creative journey. We’re proud of our latest album, Meet Me At the End of the World, and the songs that are on that project, but there’s always little moments on any record that fall short. Every writer has his or her own standards of perfection; I don’t know that we ever completely get there, but we give it our best shot.

Is there anything you’re interested in doing or exploring in the next 5 to 10 years that you haven’t done yet?

Linford: Career expectations are something we don’t put a lot of energy into. I try to stay focused on the craft and the work itself. At this stage in my career, I don’t know if that makes me an underachiever or what. (laughing) I don’t spend a lot of energy trying to figure out what’s going to happen. I just try to write the best songs I can, make interesting records, and let things unfold in real time.

Karin: For me, it’s important to just be grateful. It’s an exercise in growth to be thankful for what you’re given every day. I really think that’s a hard thing for a lot of people—especially younger people. We live in a culture where we’re taught to be entitled, and it’s a shame because you don’t have very many learning moments when you’re entitled.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

Karin: Oh my! Where do we begin? We moved out to our farm here in Ohio over eight years ago. I had a dream of opening a screen door in the morning with a cup of coffee, letting the dogs out, and casting my gaze upon nothing but trees, rolling fields, and singing birds. Linford was out driving on the backroads one day, trying to finish the songs that would become the Drunkard’s Prayer album. He rounded a bend in the road and saw an old, pre-Civil War brick farmhouse beneath a few tall trees with a “For Sale” sign stuck in the front yard. We decided to make the big move outside the city and it has changed our lives. Our house was built in 1833 and our nearest neighbor is over a half mile away, so that’s pretty much the scene.

Linford: Yeah, I think we were always fascinated by certain American writers or artists who were immediately associated with a place—people like Robert Frost, Flannery O’Connor, Wendell Berry, Mary Oliver, and Georgia O’Keefe. That place for us is Ohio. We wanted to find a piece of unpaved earth on which to put down our roots. Someplace steeped in solitude that would be a balance for, and a refuge from, our life on the road.

When we first moved out here, we didn’t know the names for anything—none of the trees, birds, weeds, or wildflowers. Before my father passed away, he helped us with some of the naming, but when he was no longer around to do that for us, we began the work of learning for ourselves. It was like learning a new poetic language. Calling things by name feels like an act of respect, like giving the ravishing earth the attention it deserves. What surrounded us began to seep into our music: all of the songs on Meet Me At The Edge Of The World revolve loosely around this place we call home—they all grew out of this dirt.

My father was a lifelong birdwatcher and he encouraged us to “leave the edges wild” when it came to fixing up our farm. That way, the birds could have secret, hidden places for their untamed music. That became an important metaphor for us, and that line appears in at least three songs on Meet Me At The Edge Of The World. When it comes to our music and the way we live our lives, we could do a lot worse than leaving the edges wild.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Karin: Yes. Again, that’s partly why we stayed rooted in Ohio. There were people here who felt like lifelong mentors.

Linford: We’ve been somewhat isolated here on the farm, and I’m sure that we’ve missed career opportunities by not living in Nashville or NYC, but we increasingly hope to create a community here on the farm as well. We had our first concerts out here, which were really quite special, and we hope to have a venue here one day for musical gatherings and workshops.

That’s wonderful. What does a typical day look like for you?

Karin: I’m up at 7:30am to feed the dogs. Then I make coffee and find a little solitude. After, I walk the dogs and then I work, write, rehearse, and garden. Most of the time, it’s either taking care of the house or packing our bags for impending musical adventures. I usually have an adult beverage at 5pm and let the dogs romp. Then Linford and I cook supper together and will eat outside if weather permits—take a good look at the evening sky, see what kind of show it’s putting on. We play it by ear, but there’s a subtle rhythm to our days. We like to have our friends out and gather around an open fire under the stars. And of course, if there is a full moon, everything stops.

What is your current album on repeat?

Linford: We’ve listened to the Milk Carton Kids’ new album, The Ash & Clay, probably more than any other record this year. It’s a great kitchen record, and they’ll be joining us on the road in September.

Our friends Kim Taylor and Lucy Wainwright Roche also have wonderful projects coming out that we’ve gotten to hear in advance. There’s some good music being made in 2013.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

Karin: We’ve gotten a bit hooked on Downton Abbey. After James Gandolfini passed away, we pulled out a few seasons of The Sopranos and remembered that feeling from years ago of never having seen anything like it on TV before. We’re pretty big public television buffs—if we get around to watching TV because we don’t have cable here on the farm.

Linford: Movies used to be so important to me when I was younger: less so now perhaps? I always used to list My Life As A Dog as my favorite film, and it probably still is.

What are your favorite books?

Karin: Jeanette Walls’ The Glass Castle. I’m a big fan of memoirs.

Linford: Probably Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim At Tinker Creek.

And your favorite food?

Karin: Oysters on the half shell.

Linford: Fresh tomatoes from the garden.

Last question. What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Karin: I’d like to be remembered as a wife, friend, godmother, dog—and animal—lover, flower gardener, singer, songwriter, raconteur, and a good laugher.

Linford: I’d like to leave some token of appreciation behind in exchange for the gift of having been alive in this world. I would like people to know that I tried to praise the mutilated world and that I found a little piece of unpaved earth and paid attention.

“Calling things by name feels like an act of respect, like giving the ravishing earth the attention it deserves. What surrounded us began to seep into our music: all of the songs on Meet Me At The Edge Of The World revolve loosely around this place we call home.” / Linford