- Interview by Tina Essmaker April 29, 2014

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Paul Sahre

- designer

- illustrator

Paul Sahre has operated his own independent practice since 1997. He is a frequent visual contributor to the New York Times, has authored books, redesigned two of Canada’s largest magazines, built and destroyed a life-sized monster truck hearse for They Might Be Giants, and appeared in a ’90s Winona Rider film. He received his BFA and MFA from Kent State University and has taught graphic design at the School of Visual Arts for 13 years.

Interview

Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I drew a lot as a kid, so that was part of my identity from a young age. My mother, who was an occupational therapist, encouraged me because she was also interested in drawing and painting. I remember trying to elbow out my brothers and sister early on for refrigerator space. (laughing)

I actually stopped drawing once I found graphic design, but drawing is what lead me into that. I originally went to school for illustration, but when I discovered graphic design, I thought, “No, no, no—this is the thing.”

Did you always know you wanted to go to school for something creative?

Sort of. In high school, I was into sports and I drew cartoons. I made a terrible comic strip for the student paper about a baboon named Wentworth, and I’m ashamed to say that it was influenced by Garfield. There’s a trail of embarrassing work that goes way back. In fact, my mom recently framed a drawing I did when I was 13; it’s a scaly monster eating human flesh. It’s now hanging right next to her front door, and she tells people, “My son did that!”

At least you weren’t putting everything online at the time, right?

No, but I guess I am now. I can’t tell you how happy I am that the Internet didn’t exist when I was younger—I don’t even want to think about what would be floating around out there. You think of it as being temporal, but it lasts longer than the paper.

Anyway, I went to grad school and that was a time of discovering what I wanted to commit to. After graduating, I had to pay off loans. My then-wife got a job in Baltimore, so we moved there and I had to find a proper design job. I found one, and I was miserable. (laughing) Miserable might be an overstatement, but let’s just say that it wasn’t like grad school. I was designing annual reports and doing a lot of corporate work. You know that feeling when something just feels right? That job did not feel right.

After two years, I left that job and started working in a small mom-and-pop design studio called Rutka Weadock. I liked it there, but I wasn’t making enough money. Out of desperation, I took a position at an ad agency where I was uber miserable. After I was finally fired, I started working for myself.

It took about six years to pay off my loans while living in Baltimore, and then I got divorced. I sold my house, sold my car, and moved up to New York—everything sort of happened at the same time. In fact, I had a to-do list on my wall that read: “Number one: get divorced. Number two: sell house. Number three: sell car.” Number four was another important one, and number five read: “Move to New York.”

Did you open your studio when you first moved to New York?

Yes, but I’m actually in a transitional phase right now. I’m moving my studio, Office of Paul Sahre (O.O.P.S.), at the end of June. I’ve been here for 13 years and, in a weird way, it has been a reflection of the feeling I had in grad school.

You’ve been in the same location for 13 years?

I have. The idea was to keep overhead low and do the type of work I wanted to do, whether it brought in money or not. That’s still sort of how I’ve been proceeding, which is part of the reason for this change. I’m still operating by my inner 24-year-old’s rules at this point. (laughing) It’s great here, but it’s too expensive now; the rent has slowly crept up.

Did you have an “Aha!” moment when you knew you wanted to be a designer?

I did, and it was in my junior year at Kent State. I just sort of started to get what graphic design was, and I had a number of good teachers. I took a class with j.Charles Walker that year; I also had a teacher named Richard Mehl. He now teaches at the School of Visual Arts here in New York, and we get together for a beer every once in a while. Richard was—and still is—the coolest guy. He seemed to be living the ideal creative life.

“There’s a trail of embarrassing work that goes way back. In fact, my mom recently framed a drawing I did when I was 13; it’s a scaly monster eating human flesh. It’s now hanging right next to her front door, and she tells people, ‘My son did that!’”

What type of work have you been doing recently?

I have focused on different things over the years, but I am probably best known for my illustrations and book cover design. Around the time I was fired from that last job in Baltimore, I started doing work for Nicholas Blechman at the New York Times. He wanted me to come to an illustration and think about an editorial the way a designer would. That started a whole new way of working that has been fruitful and interesting in that it involves having almost no time to design something. (laughing) Is it a photograph? Is it a drawing? Is it typography? It depends, but the idea and what happens when somebody interacts with it is usually most important. The word interactivity is thrown around a lot now, but almost always in a digital sense. This has always been a little funny to me: don’t we always want interaction in our work? It’s just that I usually don’t want someone clicking.”

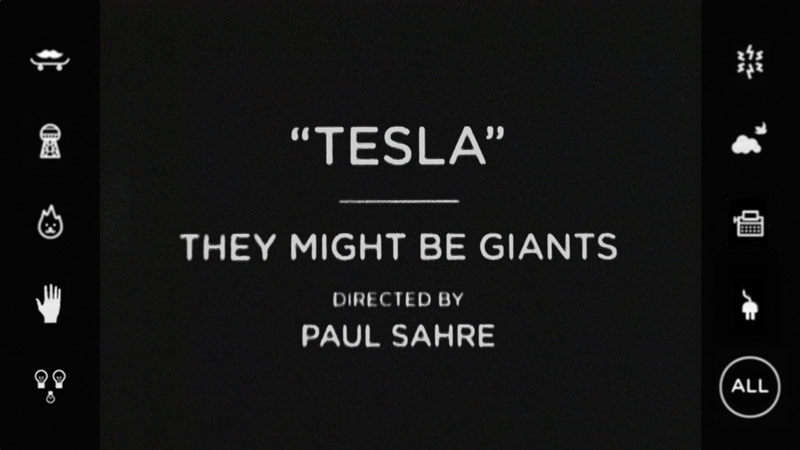

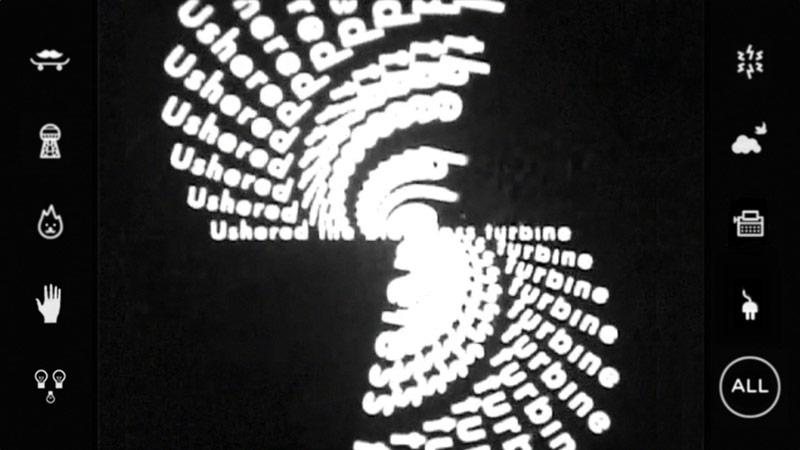

Lately, I’ve been getting back into digital and interactive design after having left it in the ’90s, before the dot-com bust in 2000. Right now we are designing a nine-part music video on Nikola Tesla for the band They Might Be Giants; we’re doing a lot of work for that band in particular. Still, I try not to specialize. Whatever I’m working on can take many different forms, and it’s much less interesting when you work on the same thing all the time.

You mentioned moving the studio. What happens after that?

I actually don’t know what’s next. The studio will either be smaller or larger than what it is right now. It used to just be me; then it was me and an intern; then it was me with three or four people, which was crazy. It then became me with a full-time person and an intern, and that is sort of what it has been recently. Erik Carter, my latest employee and a really talented designer, retired from O.O.P.S. just last week.

For years, I’ve been pursuing the same mindset of working, but with employees and as rent goes up, the bank account becomes precarious. Over time, that tires you out. We weren’t big enough to do larger projects, but we weren’t small enough to afford to do the type of work I’ve traditionally done.

For instance, I was using this space to do a lot of silkscreening: I actually started my career being interested in that. I enjoyed doing it as a 20-something when pretty much no one else, in terms of graphic designers, was doing it. People thought I was crazy; it was a disappearing form of print and designers didn’t print their own work. Back then, at age 25, silkscreening it felt like rebelling in a way; but now, at 50, it isn’t. (laughing) We went through a purge by getting rid of all the silkscreening supplies and equipment, and it was actually kind of liberating in a weird way. That part of how I used to work has been, one, not as interesting to me, but, two, difficult because I haven’t had the time for it. I think I’ll go back to it eventually, but I have twin boys now, and I haven’t been silkscreening since they were born five years ago.

“…I’m actually in a transitional phase right now. I’m moving my studio, Office of Paul Sahre (O.O.P.S.), at the end of June. I’ve been here for 13 years and, in a weird way, it has been a reflection of the feeling I had in grad school.”

Tina: have a twin brother. My parents didn’t know they were having twins.

(gasps) Wow! Yeah, that’s us: two babies at once. It’s been a hurricane through our lives.

Especially since you have two boys.

I like to joke that, at this point in my life, I need a striped shirt and a whistle—all I do all day is yell, “Hey, cut it out!” I have some experience, though. I had a younger brother, so I know what happens when your parents are out of earshot. As a parent, I used to be able to enforce certain rules because I was in the room with them, but it’s harder now.

Does one claim that the other one instigated them?

Yeah, exactly. Then they’re both in trouble. Growing up, my little brother was usually the one who started it. I would get the short end of the stick in that situation because he would be the instigator. He once took my Doobie Brothers’ Best of the Doobies cassette tape and threw it in the pool; I held him down and punched him in the shoulder or something, but we both got in trouble. Having twins is payback in some form. (laughing)

Do you live in New York City?

Yes, but we’re actually thinking about moving to New Jersey or somewhere with a yard because we’re busting at the seams.

Space-wise, I think it would be challenging to raise kids here.

It is, but when you live in New York, you really need to be doing things, right? Going to shows, eating out, etc. We don’t do that anymore. When I first came up here in 1997, I was working for myself; I first worked from home and then got a small office downtown. I made it work because I was at the studio until 11pm, happily; then I’d go out; then I’d go back to the office. Students often tell me that they’re too busy and worry about their quality of life, but I totally don’t understand that idea. I tell them, “Just pull an all-nighter,” and they reply, “What? Why would I do that?” I think, “Do you care about what you’re doing?” Sure, you have to sleep sometime, but don’t you want to keep doing this? I always did. I never wanted to go home, and a lot of times, I didn’t. I had an army cot in the back of the studio. (laughing)

You have to work hard anywhere you live, but that’s especially true here.

Yeah. The nice thing about this location is that if you’re here working, people will pop in all the time. Because there have been so many interns, former employees, and friends that have rolled through this place, it has become sort of like a hub. People often stop by to say hello. It’s nice.

“I have been wondering, in terms of work, what people do with the advantage of being in a first-world country. Do you use that advantage to make a lot of money? Do you use that advantage to help others? Do you mindlessly consume?”

Has there been a point when you’ve taken a big risk to move forward?

No, but in a lot of ways, my plan to grow the studio is way less risky than what I’ve been doing over the years. It’s expensive in New York, and it takes a large amount of money to keep an operation like this going.

It’s also tough when you love the work you’re doing because you don’t want to say no to projects.

Yeah, and that’s the reason you get into design in the beginning anyway.

If you’re trying to get rich, do something else. (laughing)

Yeah, and to a certain degree, it’s a detriment. This is a business, but I don’t think of it as a business: it’s a creative home, but I’m coming around to thinking a little bit differently about it. We’re going to use the same methodology of keeping a small footprint and not doing work that we’re not 100% invested in, but just doing it on a bit of a larger scale.

For instance, we typically don’t do any large identity projects or branding, but now we’re starting to. There are so many moving parts to the way I’ve been operating. The job list for small illustration projects is ridiculously long for only one or two of us. We don’t have the time, unless we decide, “This is what we’re going to invest our time in.” We have to work quickly, and that gets exhausting over time.

Have your family and friends been supportive of you along the way?

My friends in particular end up being the people I work with. If I have to have 20 conversations with somebody over the course of a week, I’d rather it be Michael Northrup, Jason Fulford, or a handful of other people. The idea is that your creative life is your life—it’s not separate. I can count on one hand my friends who are not involved in the creative industry. Your friends have your back and you have theirs.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Yes and no. I have been wondering, in terms of work, what people do with the advantage of being in a first-world country. Do you use that advantage to make a lot of money? Do you use that advantage to help others? Do you mindlessly consume?

I have used that advantage to do what I want creatively, to basically do what I want as a designer, but I’ve come to realize there are pros and cons to that. My graduate thesis was about advocacy; I was tackling large issues like overpopulation using graphic design, and I was interested in designers like John Heartfield. But graphic designers can be marginalized to the point where they ask, “Why are we even doing this if we don’t have control over what we’re making?” After my early experiences working for others, I decided that I was going to do what I wanted creatively. That’s been the main focus—not making the world a better place.

But in a weird way, I’ve accomplished both. My studio has a ridiculously small footprint; we try not to waste anything. Over the years, I have looked for opportunities to work with organizations that do good, or that at least don’t do bad. For years, we’ve worked with an AIDS organization here in the city; we just redesigned the interior of a juvenile probation center; and we’re designing a neighborhood in Queensbridge to increase literacy.

Frankly, you could argue that designing theater posters helps people, but it really doesn’t. It’s almost like having a collector mentality: “I designed this thing, and now I’m going to do another thing!” That’s great, but what does it mean long-term? Have all I really been doing is finding a way to be selfish?

“New York is such a condensed, crazy place. It keeps me hungry, lean, sharp, and aware in a way that I wouldn’t be otherwise.”

What advice would you give to a young person just starting out?

You can be as happy or as miserable doing design as anything else you decide to do. It doesn’t matter what it is; it only matters that you commit to it. Do you care? Can you commit? That’s it. I don’t necessarily believe graphic design is any better or worse than other careers you can choose, but I do think the dedication has to be there. Yes, there is the dignity of work, but—and maybe this is just selfishness—whether you’re a plumber, a policeman, or an architect, if you don’t look forward to going to work in the morning, that’s really sad. That’s where a lot of people end up for various reasons.

I remember a day years ago when I worked as a design director at the ad agency I mentioned earlier. I called my staff in and asked them, “What are we doing here?” I was being the worst boss ever! I said, “We’re just wasting our lives! We work all day on these shitty projects and then go home.” It wasn’t long after that the group was disbanded by one of the partners. (laughing) I kind of started a mutiny. It was beautiful.

Did you answer your own question, “Why are we here?”

I did. (laughing)

The other advice I would give is that you have to say, “No,” and you can’t be put in a position where you have to do anything. Otherwise, you’re going to be miserable. There are many different reasons why you choose to do something, but it’s always a choice.

I mentioned the analogy of my studio being like grad school. I really believe that my office has been an extension of grad school because of the freedom I have. It wasn’t easy to do, but after six years of working in not-ideal creative environments, like the ad agency, I’ve tried to make my studio different. There was an account executive at the ad agency where I worked and I used to call him The Black Hole of Creativity; he’d come into the room and suck out anything good we had going on. It was all fear and—ugh.

Because all he cared about was the money?

It wasn’t just that. Who cares? If you love making money, then show that: you can be passionate about making money. The problem was that this guy was fucking miserable—I can’t imagine what his home life was like. Maybe he was just miserable at work, but everything was about the bottom line and getting it done and there was no humor, no joy. Oh, my God, that guy! I still think about him. I don’t accept the idea that you have to be miserable to get by in this world.

Are you creatively satisfied?

Yes. I love coming to my studio: it’s a bit of a rest because I have kids at home. (laughing) If you’re doing something creative, you have to be playing a lot of the time. Right now, I’m trying to figure out how to sync a portrait of Nikola Tesla that we’ve fitted with light bulbs to a They Might Be giants song. What’s better than that? Or I might get an illustration assignment and part of it involves inventing an alien language. What would you rather be doing (laughing)?

So you’re never wanting for more?

No. Sometimes it concerns me because I have no goals. Now I look at my job with an attitude of, “What do I get to design today?”

Every day isn’t like that, of course. We just went through tax time. (laughing) I typically ignored that stuff in the past, but have come to understand the importance of staying on top of the paperwork. The photographer Tom Schierlitz, who is super organized, told me, “The best way to be lazy is to be organized.” It’s true, but it’s so not my nature.

Is there anything you’re interested in doing or exploring in the next 5 to 10 years?

I’m interested in video. The Tesla thing I mentioned earlier is for a music video we’re doing; we’re shooting it all with old 8mm cameras, so I’ve spent the last six months emailing people in Czechoslovakia trying to find old standard 8mm film stock. It’s probably been sitting in someone’s freezer for the last 20 years. (laughing) Nah, I’m sure that’s not the case, but I feel like no other person on earth would be using a lapsed format to do what we’re doing right now. There’s something great about that.

Over the years, out of necessity, we’ve become like MacGyver by making everything out of nothing. I hear other designers complaining about small budgets, but we are literally working with nothing. What can we make from the items we see laying around in the studio?

But to answer your question, I really have no idea other than I see myself still being a graphic designer.

How does living in New York impact your creativity and the work that you do?

New York is such a condensed, crazy place. It keeps me hungry, lean, sharp, and aware in a way that I wouldn’t be otherwise. In some ways, it can be tough and that can push people away. You either take it and dish it out, or you live somewhere else.

Is it important to you to be a part of a creative community?

I’m sort of a loner, but the building that my studio is in has certainly been a way of being part of a creative community. It’s going to be hard to leave. I love the building: Zut Alores! is upstairs and Karlsson Wilker is downstairs. We have helped and supported each other for a long time. Seeing their work pushes me, and I hope the stuff we’re doing pushes them.

I used to run an independent workshop with Jan from Karlsson Wilker and James Victore over at the Art Director’s Club. One year I decided to do a mass collaboration: 40 people making one thing with no rules and no hierarchy. It was such a mess! It was like Lord of the Flies. A number of people almost left the workshop because they were so frustrated and angry, which I sort of regret, but at the same time, I thought, “Really? What did you come here to do?” I learned so much from that experience, and I’m sure they did too. That’s the reason there are creative directors and junior designers; there has to be a structure.

That experiment was a microcosm of my reasoning for avoiding groups. I remember seeing a film in my 5th grade social studies class called The Lottery by Shirley Jackson. The story is about a small town where everybody gathers in the square. Everyone is worried. Each person in turn picks a scrap of paper out of a container until one woman draws one with a black mark. Then everybody stones her to death. That was how the story ended! I was in the fifth grade thinking, “What!?” Something can seem insane, but as soon as people get together, it seems rational. That scarred me for life (laughing).

What does a typical day look like for you?

Basically, I sit down at my computer, put on my headphones, and stare at the screen all day. I will occasionally type something (laughing).

I hold classes in the studio once a week and, yes, other things happen. Maybe that’s why I used to print here at the office. When you’re sitting at a computer, you think you’re jumping over tall buildings in a single bound or holding back a huge river with your bare hands, but in reality you’re just moving your finger. With silkscreening, I’d actually be sore the next day; it was a physical act. But any way you work—whether you’re drawing on a surfboard, printing, or sitting at a computer—as long as you’re engaged in the design process somehow, that’s the idea.

What music are listening to right now?

I listen to music that you probably wouldn’t want to share with anybody. (laughing) I like dollar records and I don’t listen to much that is current. But even a dollar record is new to me.

Do you have any favorite books?

One of my favorite books is The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins—just know that you might decide to change your life if you read it.

Is that a good thing?

I think it is. That book presents an argument that is depressing if you think it through. It argues that humans have ancient genetic material within us and that we are an outgrowth of that genetic material’s desire to survive. That means that our bodies, our civilization, love, hate, war—all of that—is being dictated by our DNA. The DNA is in control and we are basically large, hulking puppets. (laughing)

That is a little depressing. (laughing)

It is, but it’s also kind of amazing. It’s a shift on how we fundamentally think about things, but the book does offer some hope at the end. Dawkins also views ideas as being replicated—that’s where the idea of a meme comes from. If somebody has an idea or a thought, then it’s passed from one person to another and essentially replicated, meaning that although we are essentially controlled by our genes, we can still think outside of that reality. Also this would explain the popularity of cat videos.

Are you reading anything now?

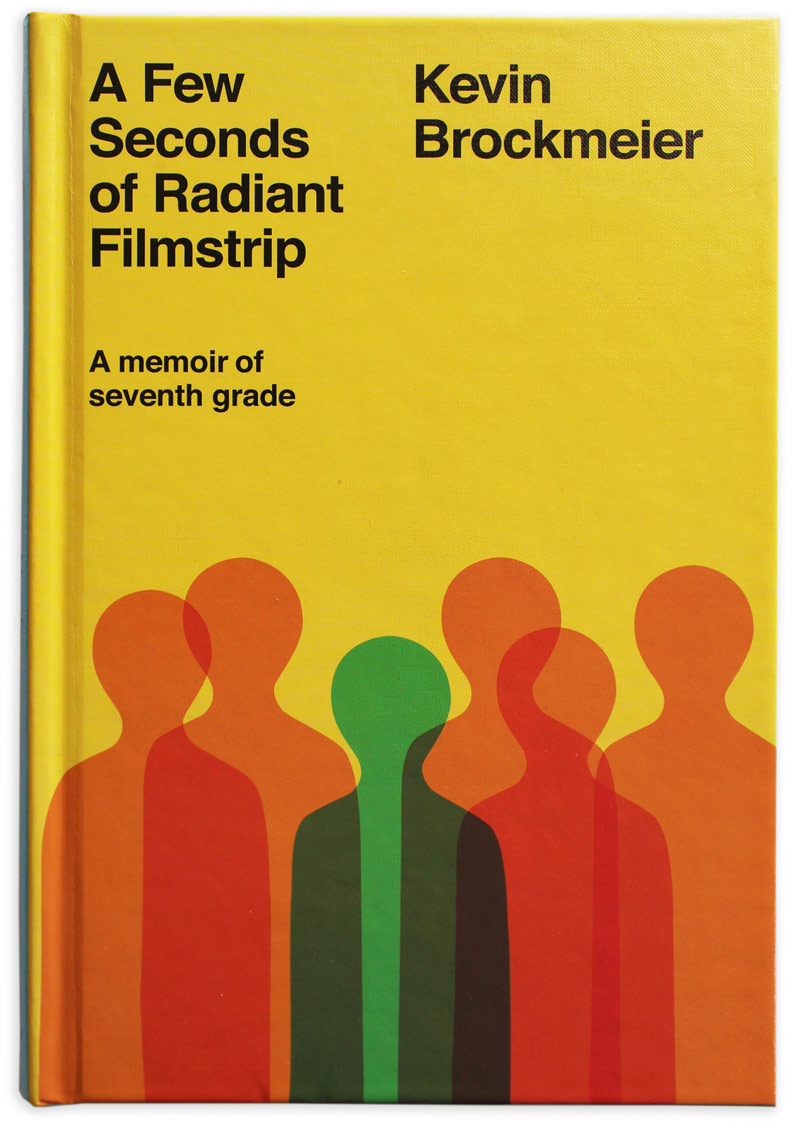

I just designed a cover for a book by Kevin Brockmeier called, A Few Seconds of Radiant Filmstrip. It’s his memoir about being in the 7th grade and it’s fan-taaastic. I also think that Zombie Spaceship Wasteland, Patton Oswalt’s first book, is terrific.

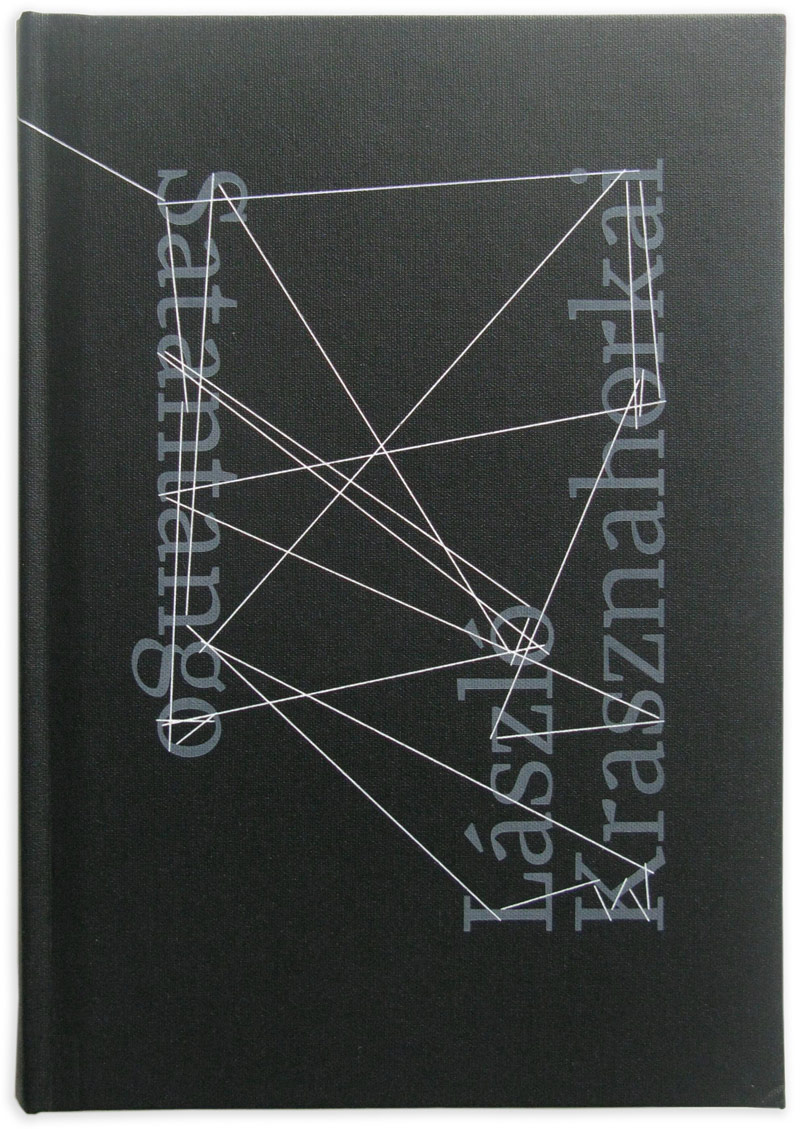

Something completely different is Satantango by László Krasznahorkai. He is a Hungarian author and that book is a new translation by New Directions—it’s incredibly bleak. There is also a fantastic film adaptation of it that is seven hours long—the opening credits alone take 30 minutes. The Hungarian director, Béla Tarr, doesn’t cut: when you see a character walk across a field, they go all the way across the field and into a house. It’s incredible.

I also like anything by Chuck Klosterman. We’ve been doing a lot of his covers, and his newest book is called I Wear the Black Hat: Grappling with Villains (Real and Imagined). His first book was Fargo Rock City, which is all about 1980s hair metal and Chuck wanting to rock as a kid in rural North Dakota. (laughing) I was not really into hair metal; my younger brother was. Even my dad, a retired aerospace engineer, loved the book; I think it helped him understand my younger brother a little better.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

I don’t watch TV, but my wife does. I watched so much TV as a kid that I do not need to watch any more, but my wife wasn’t allowed to watch anything growing up, so now she watches everything. (laughing)

I only watch kid movies now, unless I happen to be on a plane. The LEGO Movie was excellent—go see that. Avoid Frozen.

Do you have a favorite food?

I love kimchi and, sadly, anything fried. French fries!

Do you have a favorite place for french fries in New York?

No, because I avoid eating them. For food I eat all the time, go to Village Yogurt near the corner of 6th Avenue and 15th Street and order a combination fantasy with kimchi.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Before becoming a father I would have answered this question in a totally different way. My relationship to what I believe about something being permanent has changed. Can design change the world? No, there is no legacy. There’s only how you treat other people and what you do on a daily basis.

“Can design change the world? No, there is no legacy. There’s only how you treat other people and what you do on a daily basis.”