- Interview by Tina Essmaker November 4, 2014

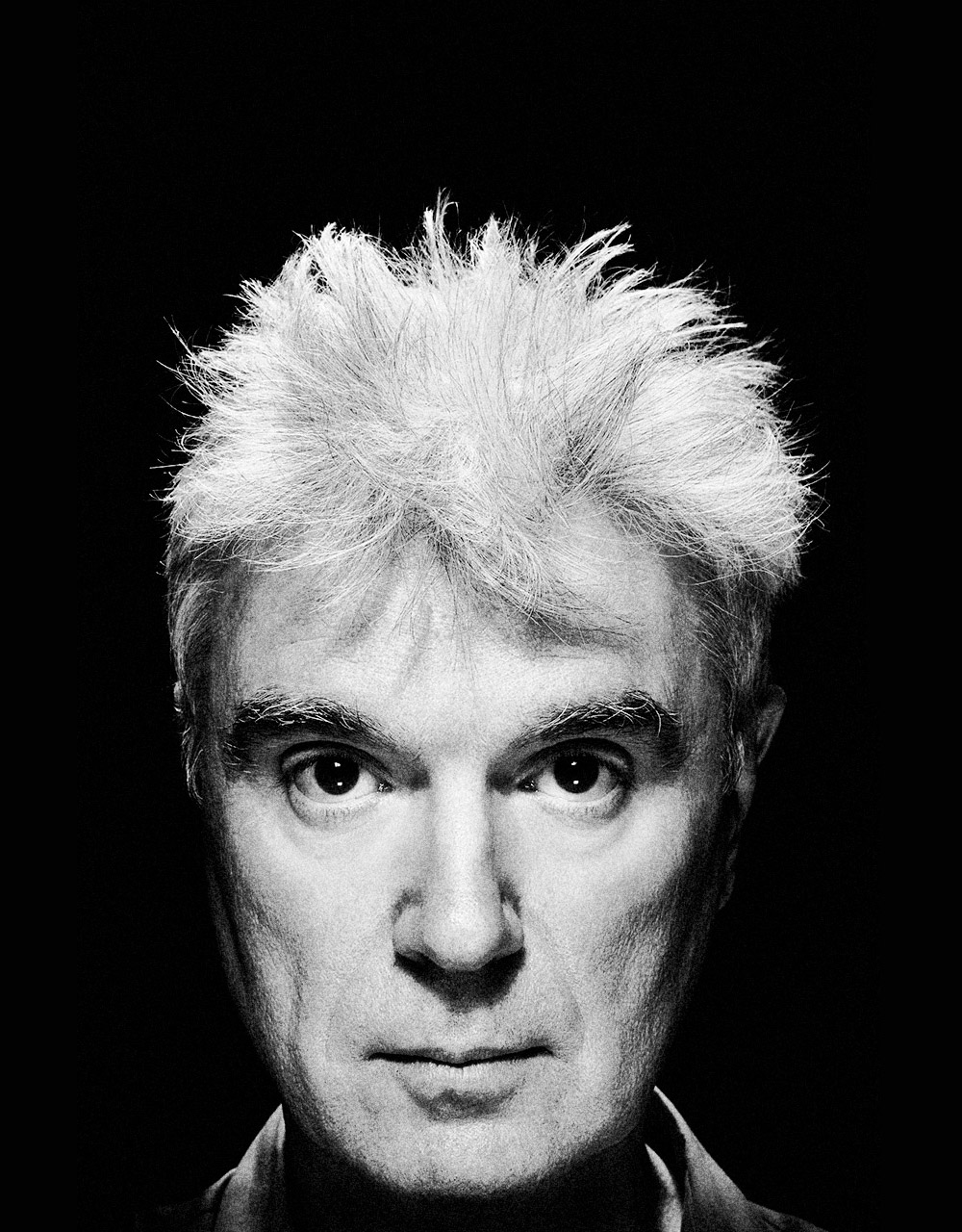

- Photo by Katie Wedlund

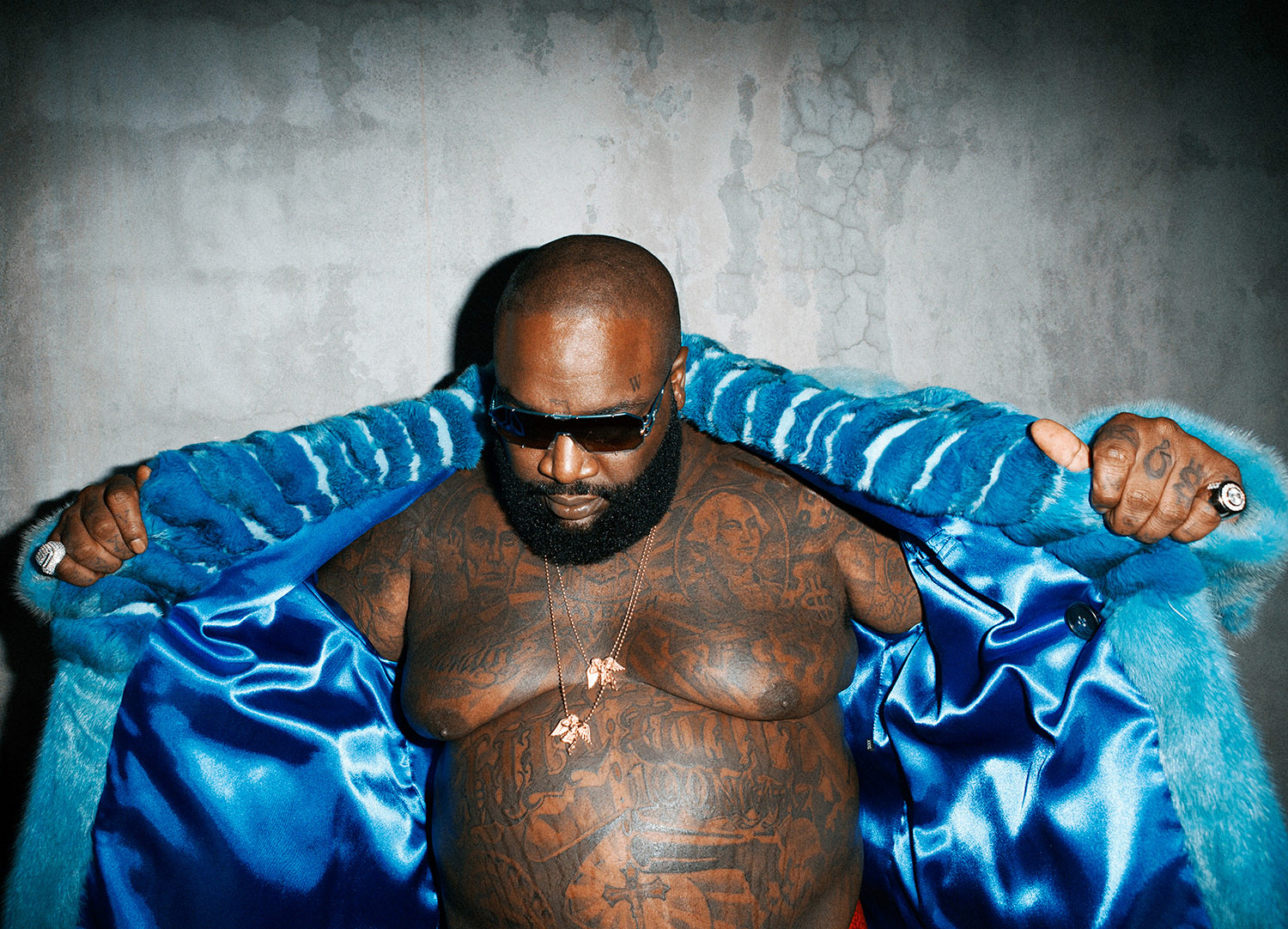

Clayton Cubitt

- photographer

- filmmaker

- writer

Raised in New Orleans, Clayton Cubitt is a photographer, filmmaker, and writer based in New York City. He mixes art and fashion with technology and is the creator of the viral video art series, Hysterical Literature. He has exhibited worldwide and worked for a variety of editorial and advertising clients, like Vogue, Rolling Stone, HBO, and HarperCollins.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Three, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Three, available in our online shop.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I grew up the child of redneck-hippie-bohemians. My mom ran away from home at 16 and was a go-go dancer on Bourbon Street; my dad was a Canadian national who ran pot over the border from Mexico to Texas, and then into Southern Louisiana. My parents met on Bourbon Street, fell in love, and went on a road trip for years and years. I was conceived on that road trip, in the back of a Volkswagen van, at Dinosaur National Monument in Utah.

When I was growing up, we lived in desert trailer parks. At one point, we stayed on an Indian reservation in the Nevada desert, not too far from where people subsequently started holding Burning Man. It was a strange, roaming childhood, which led me to desire nonstandard pathways, lifestyles, and art.

As a kid, I always fit in, but I also never fit in. I attended many different schools each year as we moved around the country. As a result, I developed tactics to quickly take the pulse of wherever I was and figure out where people’s buttons were. Later on, that proved to be very valuable in photography; you need to have that ability as a photographer, especially when you’re shooting celebrity portraiture. You have to understand people’s moods and how you can respectfully get what you need out of them.

Before I became a photographer, I was a visual artist and a fine art painter. As my paintings became more photorealistic, I began using photos as a jumping-off point for my work. But I’m a control freak, so I wanted my own source images. I picked up a camera to use in gathering raw material for my paintings, but I quickly loved how much more social photography was: I could actually interact with humans on a real-time basis and have a conversation, which doesn’t happen with painting.

Within a couple of years, I decided to go into photography. This was back in the analog days when you had to also learn darkroom techniques, film processing, and all of that. It took a while, but I taught myself how to be a photographer, and that’s how I became one.

You moved a lot when you were younger. Did your family settle down at some point? And how did you end up in New York?

We mainly jumped back and forth between an Indian reservation in the desert north of Reno and the swamps and city of New Orleans. Those were the two poles of my youth, which were in stark contrast to one another. In Nevada, there was an amazing big sky and high desert on a huge lake; it’s a saltwater lake with weird, dried rock formations all around—it looks like a Star Trek set. Then there was New Orleans and the bayous of South Louisiana, where my family is from, where my mom grew up, and where I mostly grew up.

As I said, my mom ran away from home when she was 16, and that’s the age I left home, too. I dropped out of high school in Reno and was a crusty skater punk who lived in a shitty rental behind an hourly motel where all the prostitutes took their johns. There was always some kind of drama going on. From my back window, I could see the high school I had just dropped out of. I was painting at the time and decided I wanted to make a living as an artist.

Through a series of misadventures, I got an offer from my then-girlfriend to move to Minneapolis with her. I had nothing going on and couldn’t afford to go to art school or college, so I decided to tag along with her. I didn’t know anything about Minneapolis at the time, but I was amazed at how much crazy, cool stuff was happening and how many artists I already admired were from there, like Prince, the Coen brothers, Terry Gilliam, and graphic designer P. Scott Makela.

It was easy to live in Minneapolis and nurture a more stable aspect of my personality. I had an insane childhood, and I used that time in my early twenties to recuperate and live like a “normal” person for a while. The only downside to living in Minneapolis was the insane, Siberian winters. It was crazy! During my first winter there, somebody bet me $20 that they could throw steaming water from a coffee mug up into the air and have it come down as ice chunks. I told him, “Fuck you. No way!” But it actually happened. I thought, “I’ve got to get out of here. I’m a Cajun!” (laughing)

So, you were painting, but were you also working a day job?

Yeah. That’s how I taught myself photography once I became interested in it. I started at a crappy day job at a One Hour Photo. Then I got a job at a more professional photo place, and then I worked at a camera store. Each one was a shitty day job that was designed to become a real-world college course for me so I could learn how everything worked while doing it, like a cobbled-together apprenticeship. It was also the only way to pay my bills at the time. Then I started doing photo assisting and picking up my own shoots here and there. When I became fed up with that, when it could no longer teach me anything, I thought, “I have to get out of here and go someplace where I can get to the next level.” And that’s when I came to New York.

What made you choose New York?

Well, I only had two options. I have a generally perverse aesthetic and outlook on life; I find myself gravitating towards weird and elite and subversive. I couldn’t stay in a place like Minneapolis because, as cool as it was, the market for what I could do as a photographer was very mainstream. My only two real options at the time were Los Angeles or New York. As tempting as Los Angeles was, I talk fast, I walk fast, and I’m kind of angry a lot, so I have to be someplace where that’s appreciated. (laughing) New York was it.

How long have you been here?

I moved here in 1999, so I’ve been here for almost 16 years.

That’s the year I graduated high school. (laughing) This is a side note, but I previously worked with runaway and homeless youth for 12 years, and it’s super compelling to hear about your experience of leaving home at such a young age.

Yeah. After I left home at 16, my mom left a relationship that was violent and worked as a caretaker at a domestic violence shelter in Reno. It was in an old, somewhat Lynchian, roadside motel. I worked day jobs and was out on my own, but I visited my mom at the shelter. It was an oasis for multiple generations of runaways, who were trying to heal from so much tragedy, but still tied to it in such a deep way that many couldn’t escape.

Poverty is a multi-generational poison, and society doesn’t do much to help it. You’re forced to make your own way, and not everyone can. I was just extremely lucky: every day, I think, “There but for the grace of God.” Despite not being religious, the thought behind that is incredibly true. I’m privileged: I’m a cisgendered white male, I can draw, I can take pictures, I can communicate well, I had at least one parent devoted to me, and I don’t have fucked up teeth. Also, I could have a thick-ass New Orleans accent. My family has it, and I love to hear it, but, at a young age, I recognized that people are judged based on regional accents, and that judgement carries real consequences. By watching television, I taught myself how to speak like a “normal” person, code-switching, basically. I was able to escape that generational traction because I was fortunate to have some tickets out of it, and I tried to keep my shit together so I wouldn’t slide back.

Wow. Thank you for sharing this. If there are any young people reading this who are struggling, may it give them a sense of hope.

Yeah. To any kids out there who might be reading this: Fucking hang in there. Stick with it. Do your thing. I dropped out at 16, I never went to art school, and I taught myself everything I know. The only way I did it was by sticking to what I was doing and staying away from fuck-ups. There are great kids who are in trouble, and then there are kids who are fuck-ups who are in trouble; when the great kids get stuck with the fuck-ups, they get dragged down. It’s really tough, and that’s where a good social safety net comes in. This is where our country is failing because it throws all the kids into one bag and says, “Ya’ll have to claw your way out.” That’s some Hunger Games shit.

“My first big break as an actual shooting photographer was hilarious, especially considering that I was still super punk looking and had a blue mohawk: I was hired as the last staff photographer for Seventeen Magazine’s in-house studio.”

Yeah, it is. So, when you came to New York, where you still working day jobs or did you get into photography right away?

I had a portfolio with work I had done on the side in Minneapolis, but it was clearly a secondary market type of portfolio. It had lesser models and lesser fashions—everything I could gain access to for free in a smaller town like Minneapolis. The aesthetic was NYC-level, but people don’t judge photography solely on aesthetic, especially fashion and celebrity portraiture. You need to have world-class models and designers and faces. When I got here, I did photo-related day jobs within the industry, assisted for some big photographers, and did little shoots here and there when they came up.

My first big break as an actual shooting photographer was hilarious, especially considering that I was still super punk looking and had a blue mohawk: I was hired as the last staff photographer for Seventeen Magazine’s in-house studio.

No way!

Yeah. So I’m this punk-as-fuck ex-runaway working as a staff photographer for Seventeen Magazine, which essentially involved shooting everything from fashion to portraiture to makeup, shoes, and bags. We did it all, from tabletop to large format to documenting 9/11, which I did a portrait series of the local firehouses for. I did a variety of work, which was perfect for me because I hate doing one thing. As weird as it was to be in that environment considering my aesthetic, that platform was a fascinating exercise in flexing different muscles. After a year at Seventeen, I had enough money saved up and had been in New York long enough to go out on my own. I’ve been freelancing since then.

What kinds of projects are you focusing on right now?

I’m voracious with what I’m curious about. I didn’t get into photography to shoot one thing over and over. I jump around a lot based on what opportunities are present, what I’m interested in, what I’m curious about, and what gets me fired up. I shoot everything from music videos to celebrity portraiture to fashion work to documentary-based personal projects. I like doing it all at once. This used to be a drawback, like “Jack of all trades, master of none,” but clients are increasingly looking for versatility, an ability to switch between different shooting styles, and an ability to deliver audiences on social media. That all fits perfectly with the style I’ve always had.

So you’re doing photography and film-based projects?

Yeah, stills and primarily short-form stuff, like music videos, advertising, and my own personal projects that are video-based.

Like Hysterical Literature?

Yes.

You actually spoke about Hysterical Literature last night at YouTube, which is awesome.

Yeah, it is. I’m pleased that YouTube invited me out because Hysterical Literature is a project that is weird enough and subversive enough that it certainly doesn’t fit the “brand image” YouTube has of itself. But there are people there, like Tim Shey and Nicole Emanuele at the NYC headquarters, who are trying to promote more artistic uses of the platform and encourage “serious” artists to use it more. They’ve been great champions and have just built a fully equipped studio for creators to use, for free. That’s putting their money where their mouth is.

Was creativity a part of your childhood, or was it something that was encouraged?

I didn’t have an excellent traditional education. My mom certainly didn’t, either; she’s also a public high school dropout. My grandparents never even made it to high school, and my grandfather couldn’t read a word. But when I was young, my mom instilled in me a love of books, and I developed a constant desire to read. We used to walk miles to get to the library when we didn’t have a car. The library was like our church: going there was worship. I credit that with my ability to teach myself a wide variety of arcane skills. That’s also what enabled me to feel confident that I could have a voice and say what I wanted in a way that was effective, despite my socio-economic circumstances.

My mom also encouraged my artistic leanings at an early age. There’s obviously the cliché of your first gallery show being on the refrigerator when your mom puts up your work, but it’s true. That’s another reason I was able to achieve escape velocity: many kids in my circumstances didn’t have one parent, let alone two, who could help them pull it together. I was lucky enough to have one parent, who acted as mom and dad at the same time, to encourage all my weird ideas. She had it really hard, but she also tried really hard.

This is going to sound weird, but keep the context in mind: this was in the ’70s during the sexual revolution and feminism. My mom was a super indie, rebellious, feminist hippie, and she had a subscription to Playboy because she liked the articles—and she was also going to maybe be a Playboy Bunny. She had been offered a position at one of the clubs, but didn’t take it because we were on the road. Anyway, she had a subscription to Playboy and she decorated my crib with centerfolds. The first art on my wall was centerfolds! (laughing)

No way!

Yeah. Later on, when I started drawing, I used Playboy centerfolds as nude models to draw from. Kids are so spoiled these days: they have Internet porn on their phones! But this was before little boys could get porn, and I had access to it. I drew Playboy centerfolds, took the drawings to school, and sold them to the rich suburban kids. That’s how I made enough money to buy the ’80s swag I wanted. I had Polo and Generra shirts because I was selling drawings for $10 or $20 bucks a pop. (laughing)

You were a budding entrepreneur. (laughing) Was there an “Aha!” moment when you knew you wanted to do photography?

Not until a little later. I was influenced by movies and music videos, but they seemed far away and inaccessible; drawing was accessible, and direct. And I got positive feedback from my biker family, all prison-tattooed out, who saw my drawings and gave me respect. And we never had cameras, except this shitty 110 camera. We got the film developed when the roll ran out and we could afford to, so we’d get it back and it would have three Christmases on it. At first, photography seemed too remote and expensive to be something for me to aspire to.

But then I saw two photographs that made me want to quit painting and take up photography. One was an advertising photograph taken by Nick Knight for a Yohji Yamamoto campaign; it was called “Susie Smoking.” I was 17 or 18 when I saw it, and it struck me. It was so painterly, yet so crisp and alive in the way that photographs are and paintings sometimes aren’t. It had such saturation of colors and technique married to emotional intent that, when I saw it, I almost felt like I was having a stroke; it was like Stendhal syndrome. I thought, “Fuck painting. I want to do this.”

The other photo that was highly influential was “Green Room Murder” by Helmut Newton. It depicts a topless ’70s fashion model with wild orange hair in heels. She’s shown astride a seemingly dead businessman in a richly-saturated, all-green modernist room, and she’s holding a pillow over his head. I thought, “That shit is badass.” It’s an amazing image, so cinematic, and it was printed in a giant magazine and seen by more people than will ever see the average painting in a gallery. It made me realize that photography was the way to go.

So, I just had to figure out how to go from broke runaway to NYC fashion photographer. Somehow I did it. The journey would have been about ten times faster if I had started out today, thanks to the Internet and digital photography revolution. Some days I feel like I apprenticed as a luxury carriage craftsman at the dawn of the automobile era. I would have preferred to start ten years earlier, or ten years later, but we don’t get to pick our times.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

Mentors are hard to find when you’re an autodidact and on the outskirts of society. There’s a path for that for kids who go to school. They’re hooked up with mentors and, in some sense, that’s the main reason for school.

My self-education involved the materials, practice, and book side of what you would get from an art school, but it completely missed the mentorship and social or business connection side of what you would get if you went to Parsons, School of Visual Arts, or one of those art schools. I never had the opportunity for someone to say to me, “Here’s this person who’s doing amazing things in the field you want to work in, and because you’re in our institution, they’ll take you under their wing.” I would have had to basically stalk someone’s studio as a homeless kid, saying, “Yo, give me some art lessons!” I’m also a bit of an introvert, and I never would have had the hustle to do that—at least not then.

I took the energy that would have gone into finding mentorship and put it into my own weird, cloistered version of self-education. All of my mentors were intermediated through the materials I searched for, from punk music to art books. Besides Nick Knight and Helmut Newton, I loved the work Peter Saville did for Factory Records. Later on, I discovered Disfarmer and Malick Sidibé and Deborah Turbeville and Araki. All of those elements came together and formed a sort of virtual mentorship that I curated for myself.

You have to be sharp when you teach yourself, and I’ve found that it has helped me in my commercial work. A lot of projects come together in a short timeframe and have a constrained budget. I have a long history of doing everything myself; I was supporting myself when my peers were just learning how to drive. Because of that, I have a deep understanding of how budgets work. I don’t go past deadline or over budget, and I attack problems quickly because I come from a background where I had to figure shit out for myself—there was nobody around to come save me if I didn’t.

Has there been a point when you’ve taken a big risk?

I don’t look at things as risks because I do what I’m meant to do. I don’t fuck clients over; I don’t take a job and not deliver on what I promised. However, I definitely don’t take jobs that disagree with my aesthetic or feel internally compromised. I’ve taken risks in that I’ve said no to many projects that have blown up and would have been big for me. Over the years, I have passed on a lot of money, but if I had wanted to get into a career to maximize my money, I would have gone into banking. I want to take the long-road approach to what I do. What I’m doing is not a sprint; it’s a marathon. I’d rather focus on what’s meant to be, what’s organic and real, than chase trends or cash.

We’ve been self-publishing for a couple years and our growth has been organic. We’re building relationships with the people we interview, and we interview them because they’re awesome and we want to tell their stories. There’s something to be said for letting things growing organically.

That’s the thing I love about the emergence of these networked technologies. I love that DIY can become a path for success and truth and beauty all at the same time. You no longer have to make a deal with the devil like you had to in previous generations. Don’t get me wrong, there’s always a devil, but we’ve got more paths around him now.

“I love that DIY can become a path for success and truth and beauty all at the same time. You no longer have to make a deal with the devil like you had to in previous generations…there’s always a devil, but we’ve got more paths around him now.”

I like to give Millennials shit because it’s fun, but I feel like I’m a Millennial; I believe that Generation X was just early Millennial. When we look back on this time period, I think we’ll clump Generation X and Millennials together because a lot of what Millennials are doing—and are forced to do because of the economic circumstances and societal shifts—is stuff that Generation X also had to do. Generation X was very DIY with punk rock and the zine culture; it was a time when you could write your little magazine, do your own photography, put it together, Xerox it at Kinko’s, and hand it out to your friends. All of that is still happening, but now it’s happening with rocket fuel: way faster, harder, and further. It’s the same kind of culture that I aspired to and grew up with as a kid, but now it has been hyper-accelerated. Now you’re able to reach anybody in the world, instantly. (snaps fingers)

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I think we all do, and our main responsibility as artists is to put beauty into the world, stuff that’s true and isn’t fucking with people. There are enough people willing to pay good money for pretty lies; we’re overstocked with pretty lies. I’m interested in creating beautiful truths, which I think the world could use more of. A beautiful truth doesn’t have to be a subject that looks good; it just has to be honestly handled.

In this world, I think the creation of beauty is an uplifting act that can help people. Creating beautiful images that people can see, share, and take solace in is a laudable social goal. When I was a kid and living in squalor and turmoil, I certainly didn’t want to look at a gritty, “deep” documentary image of depression; I wanted to see something that took me out of my pain. That’s the kind of stuff that saved my life. As a result, I find that while my work often has an undercurrent of darkness, there’s always something beautiful and aspirational about it.

Are you creatively satisfied?

Never. I don’t think there’s been a moment in my life when I’ve been creatively satisfied. Maybe there’s a sliver of creative satisfaction in the moment between when I have an idea and when I have to make the idea: I have an idea, it’s in my brain, and it’s perfect. As soon as I start making it in the real world, all satisfaction goes out the window and will never return. No matter what I do, the thing I make will be different than what I had in mind; there’s the original fantasy and the final execution.

Are there any projects you’re interested in exploring?

Anything that challenges me, and lets me challenge others.

I’m interested in a lot of subjects, but I don’t think we’re quite there yet technology-wise for some of those things I’ve dreamt about lately. For example, I’m quite fascinated with how Google Street View, Oculus Rift, and other virtual mapping and networking technologies might relate to photography and art. Right now, we’re at the end of the beginning and are ready to have access to these technologies that will take photography to new realms. I’ve said this before, but I think that, pretty soon, having a camera will be as relevant to being a photographer as having oil paints is to being an artist. I don’t think it’s going to matter.

I want to be in a world where I don’t have to have a camera between my face and the subject in order to capture the subject in a way that’s real. I want to have a network of sensors that allow me to shift in time and place, anywhere, at any time. I want to say, “I was walking down Fifth Avenue the other day and I saw this amazing old man walking down the street. I didn’t want to interrupt him, but he deserves to be immortalized for the beautiful moment that he allowed me to experience.” I want to be able to get on my phone and say, “I was here at this time,” and go there and access the sensors that are there and find that old man walking down the street and take a picture of him three days later—and I want to be able to see it from different angles and change the filter on it. These things are going to be doable; it’s just a matter of time. That’s what I want.

I say all this even though it would make the skills I’ve learned for two decades obsolete. But as digital was coming along, I had learned really intensive century-old analog film and chemical-based techniques, which became obsolete almost overnight. I didn’t lament that. I thought, “Fuck it! Digital is awesome.” I sold my darkroom and all my film cameras and never looked back. When this other thing happens and we move to distributed network photography, I’ll get rid of all my digital cameras because won’t need them anymore; I’ll have the whole world.

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

I don’t know. I hesitate to give advice because my circumstances and background are so unique. I don’t know how well my advice applies to the average person out there, but I think there is some universal advice that people should stick to. It’s often a cliché to say, “You should do what you love,” and it’s certainly a piece of advice that’s hard to follow when you come from a background like mine. There was all kinds of shit I wanted to do when I was 16 that I couldn’t afford to do; if I’d done that stuff anyway, I would have starved to death. You have to balance doing what you want with making a buck, which is hard. But if you do what you love and keep that as a goal in your work, you’ll find that people will eventually come to you for it. Instead of you going to them for money, they’ll come to you with money and hire you for who you are.

Don’t lie about yourself. And never lie to yourself. Find the thing in you that is different, that’s as sharp as a diamond and jagged as a razor. Hone that, because that’s the thing with which you’ll cut the world. If you try to stay a safe and soft and average, then you’re going to get lost in the sea of all those other things that look just like you. Find the things about yourself that are weird and cultivate them because, eventually, those are the things the world is going to want to reward you for and that will bring you the most happiness. When you’re young, those are the things that cause you so much pain, but it’s that pain that makes you unique. Own your scars.

“You have to balance doing what you want with making a buck, which is hard. But if you do what you love and keep that as a goal in your work, you’ll find that people will eventually come to you for it. Instead of you going to them for money, they’ll come to you with money and hire you for who you are.”

That’s really good. So, you’re in New York. How does living here influence your work?

I don’t know if New York directly influences my work as much as the idea of New York does. The idea of New York is the only thing about New York that still exists for most people now.

You’ve watched it change over the past 15 years?

I’ve seen it change a lot. I mean, don’t get me wrong. It’s still New York. There are still moments when I think, “That is so fucking New York!” But there’s definitely been an influx of people who haven’t accepted the responsibility of New York. It’s not about preferring a dysfunctional New York; I don’t want to live in a city where I’m afraid of getting shot in the face. That’s why I got out of the ghettos of New Orleans: too many friends and relatives were murdered and it was too dangerous to do what I wanted to do and be who I wanted to be. But I also don’t want to live in a place where all the cool venues are replaced by bank branches or Starbucks. I think that New York has tipped into a realm where there are a lot of rich kids coming here for a couple years to pretend they’re bohemian before decamping back to whatever suburbs their families are from. As a result, a lot of the sharp edges of New York are getting rounded off. The latest round of arrivals no longer even dream about the bohemian city that welcomed me. They’re actively happy with the bank branches and Starbucks, and they have no problem with $15 cocktails at “dive” bars that previously catered to minimum-wage workers.

But the idea of New York as a place where anybody weird or poor can come from anywhere to be anything they want—that idea is a localized version of the American Dream. I love that. It’s very aspirational to me. I experienced that while moving around so much growing up. If I moved to a different school, I could be a different kid; if the last school sucked or I got into a rut, I could try a completely new thing. That influenced my work as well. That’s why I’m so voracious with all the subjects I like and why I refuse to specialize in one thing: I experienced the freedom of being able to be anything I want, and I want to continue to have that freedom. That’s the thing about New York that I most relate to and want to keep alive. It’s still here, despite all the changes, but every day it fades a little more, and that makes me sad for the next generation.

Is it important to you to be part of a community of people and do you have that here? It sounds like you do.

I do. It’s really important to have a crew of people around you to draw inspiration from, whether they’re physically around you or on the Internet. I have those people, and I’m lucky to be able to collaborate with them. First and foremost is my wife, Katie Wedlund, who’s a makeup artist and excellent photographer in her own right. She’s my sounding board and consigliere and partner in crime in everything.

I also have some amazing friends and fellow troublemakers who are doing next-level stuff: Molly Crabapple and Stoya—both of whom I’m currently working on something stunning with—the musician Kim Boekbinder, digital artist Justin Maller, writer Susannah Breslin, and blogger Xeni Jardin. Internationally, there’s the writer, Warren Ellis, and South African rappers, Die Antwoord, who I’ve collaborated with for years and who are the essence of DIY. I have a crew in New Orleans, too. A dear friend of mine, Rusty Lazer, a DJ and drummer and impresario, does a lot of evangelizing for the New Orleans arts community. He brings a lot of people in, infecting them with the spirit of New Orleans.

Do you travel back to New Orleans often?

Yeah, as often as possible. I go back a few times a year for extended trips.

I’ve never been.

You gotta go! New Orleans is gorgeous in the fall and Mardi Gras is also a good time to go. Mardi Gras gets a bad rap because people have a perception of it as bros on Bourbon Street yelling at girls to flash their tits. There’s some of that, but that’s such a tiny part of it; it’s like looking at Times Square on New Year’s Eve and saying that’s all of New York. Mardi Gras itself is a six-week run of social events and generalized insanity, whimsy, and beauty that’s distributed across the entire socioeconomic strata, from top to bottom. Everyone comes together, does their thing, and makes magic.

New Orleans is like a time capsule; it’s a point on the map where, in moments, reality is suspended. It’s a spooky place that respects traditions that date back to the 1700s, but, at the same time, is into remixing modern culture. The way that classes and races mix and come together in this gumbo is something I haven’t seen in many parts of the world. When you go to New Orleans, you have to keep in mind that it’s not a North American city. Don’t get me wrong; it’s as American as apple pie—well, maybe a spicy apple pie—but in its attitude toward life, it’s more like a Caribbean city, a really well-functioning Caribbean city. If you go, try to be respectful of that tradition. The $15 cocktail “dive” bars are already popping up in New Orleans, and that’s something my street-fighting granddad would be rolling over in his grave about. But go! Go and be funky.

For sure. Alright, I have one last question for you: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I don’t really give a fuck about a legacy. There was so much violence and death around me when I was growing up, and it taught me to take solace in friendships, pleasure, and the beauty around me—right now. Those are all performative acts, experienced in the moment. I’m not worried about whether or not the things I’m making now will survive after I’m dead or 100 years from now. I’m not even sure that people will be around in 100 years, and I’m okay with that. I think there’s something beautiful about the idea that we can be like butterflies: we can be here for a time, cause beauty, be admired, experience great wonder and spectacle, be great wonder and spectacle, and then we can be gone. Us being gone is not a loss; it’s just part of the process. We don’t sit around fretting about how the world was before we were born, and I don’t think it’s useful for us to fret about how the world will be after we’re gone.

Be here now, care for people, make beauty, leave it better than you found it. End of story.

“I think there’s something beautiful about the idea that we can be like butterflies: we can be here for a time, cause beauty, be admired, experience great wonder and spectacle, be great wonder and spectacle, and then we can be gone.”