- Interview by Tammi Heneveld May 24, 2016

- Photo by Dan Pask

Gavin Strange

- designer

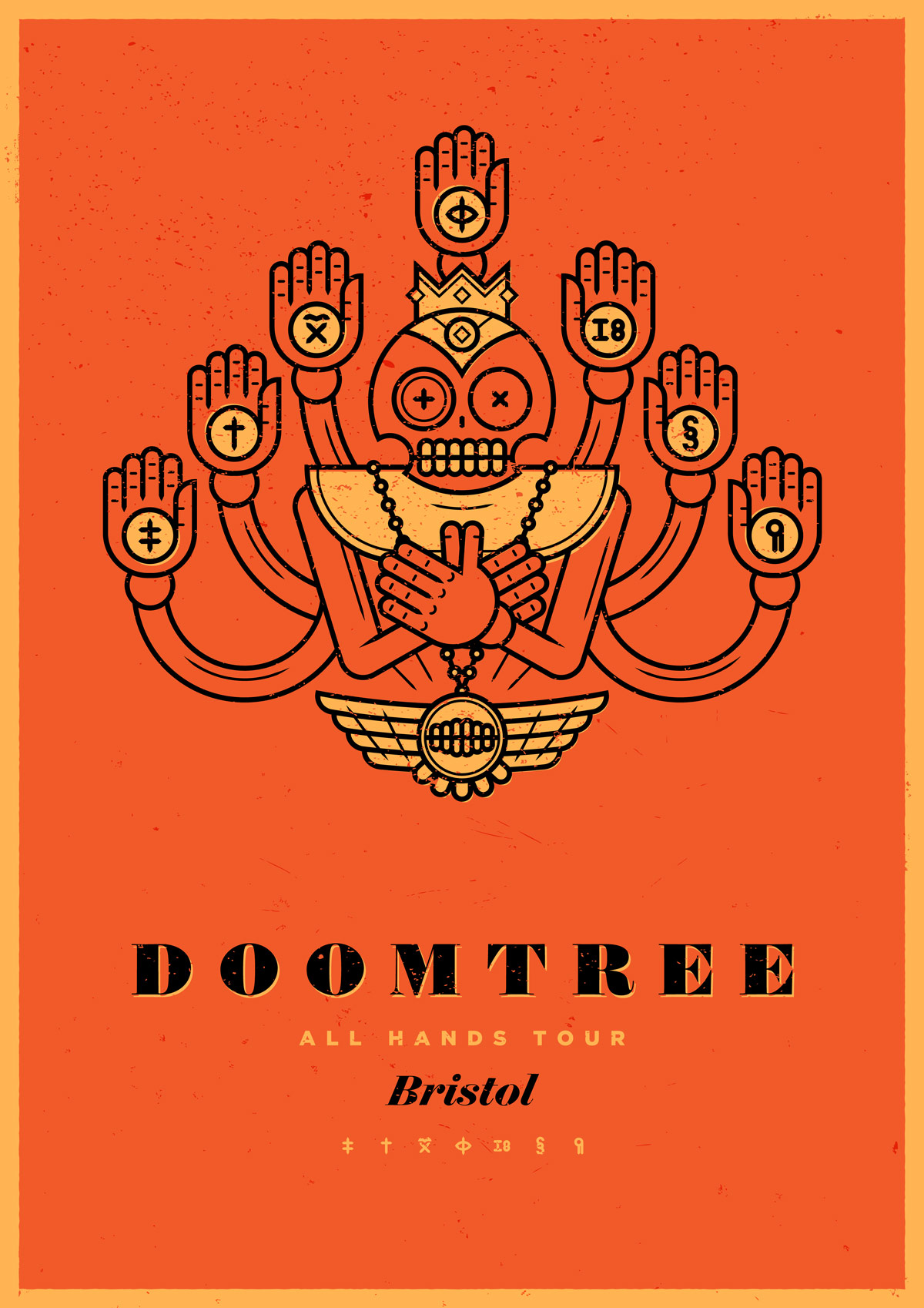

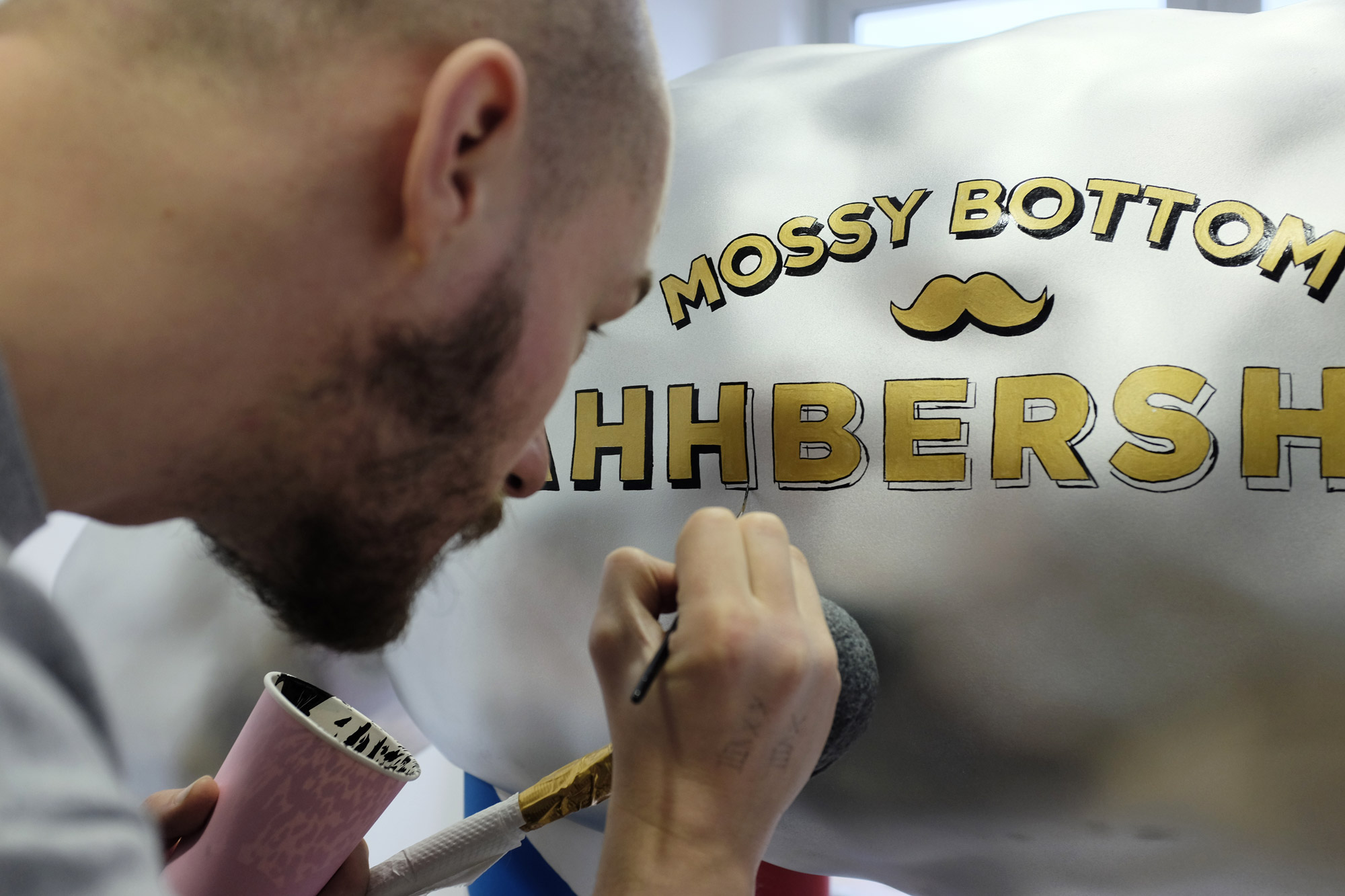

Gavin Strange is a multi-disciplinary senior designer at UK-based animation studio, Aardman Animations, and established his side-project studio, JamFactory, in 2001. Over the course of his career, he has worked on personal and commercial projects encompassing everything from branding to web design, animation, film, product design, illustration, sculpture, and anything else that catches his fancy. His book, Do Fly, released as part of the Do Book Company pocket guide series on May 5, 2016.

Describe your path to what you’re doing now. I grew up in a town called Leicester and became interested in art and graphic design in secondary school, which is basically middle school in the UK. I liked graphic design, but I didn’t understand the application of it.

Here, people generally go to college for two years when they’re 16, and when they turn 18, they decide if they’ll go to university and get a degree. It wasn’t that I didn’t have aspirations at that age—I didn’t understand what was out in the world for me to pursue. I wasn’t someone who had known his passion since I was a child. I knew I enjoyed art, design, and making things, so I chose to attend a two-year design college after secondary school. I didn’t have a big plan or vision, but I thought it looked fun.

My work was truly rubbish in college. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I applied Photoshop fire effects to everything. (laughing) Looking back, I was finding my voice. I hadn’t been exposed to anything like that before, so I was excited to learn and experiment as much as I could in school.

I feel like most people’s student work is pretty tacky, myself included. (laughing) Did that encourage you to pursue design after graduating? When it was time to decide whether or not to attend university, it didn’t appeal to me. I wasn’t very academic, and I assumed it would be all about partying, so I chose not to go. My only other option was to get a job, so I decided to go into the design industry. I heard that a design company in the Midlands called Christon Davies was looking to train a junior designer for two weeks, so I applied along with another kid who also didn’t want to go to university.

That job was the first time I’d ever been in a professional work environment, and I loved it, although I was utterly terrified. I was only 17, and everything was overwhelming. I tried not to ruin anything and stay out of trouble. After two weeks, the design studio said they’d choose one of us for a full-time position. I don’t know if this is true or not, but I was told that the reason I was hired is because the other kid used up all of the creative director’s favorite black pens. (laughing) So I like to think that I got my start in this business because I have good pen management.

I started at Christon Davies in 2000 and couldn’t believe that I had a creative job. It was a very small studio, so they weren’t looking for the next big thing: they wanted someone who was positive, enthusiastic, and willing to learn. I didn’t feel like I knew anything, so I wanted to learn as much as I could.

At that point, the internet was only sort of a thing, and I had been mucking around with making my own websites and experimenting with code in my spare time. One day, my boss said, “Would you like to be a junior web designer? We’ll teach you how.” I liked print design and illustration, and applying those kinds of ideas to the web sounded exciting, so I said, “Sure!” I still lived with my parents at the time since I wasn’t attending university, so I went home that night to tell them about the web design job. I remember my mom said, “Yeah, it sounds alright, but do you think this internet thing will last?”

Did you know what you’d be doing when you first started? I had no idea what the work would entail, but I realized that my knowledge was in my own hands. No one was going to experience it for me or hand me the skills I needed: I had to jump in and do it myself.

My boss took me aside and said, “You need to create your own website so you have a place to experiment with the stuff you’re learning here during the day.” It sounded cool, so I decided to buy a domain name. I thought of creatives I admired, like 123Klan and The Designer’s Republic, who had alter egos for their practices. I decided to come up with one for myself: JamFactory.

Once I created my website, I suddenly had a place to call home. I redesigned it every week: I’d become excited about whatever I was doing at my day job at the time, dive deeper into it, and change my own website to reflect what I had learned. The plan wasn’t to build anything grand—it was to play and tinker and see where things could go within the context of my own enthusiasm.

Over time, I also became interested in photography, film, and illustration, so I used my website to share those types of projects, too. I wasn’t born with natural talent, so I was really proud of myself. I was so stoked that I’d managed to make anything that I would unashamedly share it on my site, which would inspire me to do it again and again. It became a feedback loop, and I was gradually getting better over time. I’m 33 now, but I still feel that same type of excitement that I did at 17.

At a certain point, I became interested in skateboarding, so I started painting and designing my own skateboards. I had been helping a friend of mine, the owner of a skate shop in Leicester, with his website for a while before he said to me, “Have you ever thought about working for yourself as a freelancer? You clearly want to do more than just web design.” My first thought was, “No, that’s what other people do,” but after thinking about it for a while, the idea became more exciting to me.

I was pretty happy with where I was at age 22. I had been at Christon Davies for four years and loved it, but the possibility of going out and making it on my own was very enticing. One day, I came into work and, trembling, said to my boss, “Um, I’m handing in my notice and I’m going to go freelance!” They were kind and supportive. Even though I clearly didn’t know what I was doing, they wanted me go out into the world and figure it out.

When I made the leap to freelancing, my friend from the skate store offered me a deal: he’d give me my own office above the shop and I’d work on his website three days a week and have the rest of the time for my own projects.

So it was almost like having a patron. Exactly. Because I lived at home, I could afford to pay rent for the office. And since I was based in a little independent area of town, people heard about this young lad who could make websites for people, so I was able to find clients pretty quickly. A decade ago, it wasn’t that easy to find someone who knew how to build websites, so it was quite a mystical art.

I freelanced for four years and enjoyed it. Making websites was my bread-winner while I continued to try my hand at other mediums like filmmaking, photography, art, and design. In the process, I ended up moving to Bristol, where I’m currently based. I was a big fan of an incredible artist named Mr. Jago, who lived there. We were introduced by my friend who owned the skate shop, and I asked if I could make him a website for free since I was such a huge fan. When I came down to Bristol to work with him, I fell in love with the city. Mr. Jago was my first friend in Bristol when I moved there, and he introduced me to lots of inspiring designers, artists, photographers, illustrators, and filmmakers. Through him, I was able to build up a network of people who inspire me.

By 2007, I had strengthened my portfolio with a wide variety of projects, both personal and commercial, and I worked hard to share my work in as many professional networks as I could. One day, I received an email with a subject line that read, “Hello from Aardman.” Aardman Animations is the film studio that made all of my favorite movies and TV shows growing up, like Shaun the Sheep, Chicken Run, and Wallace & Gromit. I’ve admired their work my entire life, and they happen to be based in Bristol. There was a newly formed web division within Aardman that was still in it’s infancy—the team was about five people—and they were looking for a web designer to help out with a freelance project! I replied straight away, met with them, and was hired to work on a six-month job for the UK broadcaster, Channel 4.

It was a great experience, and I was in awe of Aardman’s studio and everyone who worked there. After six months, a full-time senior designer position opened up. My creative director, Dan Efergan, asked me about taking the position, but I remember thinking, “There’s just one catch: if I take this job, will I lose everything I’ve worked so hard for on my own?” I had spent almost 10 years building up JamFactory, and I was proud of that. Did that mean I had to throw all of that away? Luckily, Aardman was supportive of me continuing to work on personal projects in the evenings. I felt excited about the prospect of working for the people I admire most while still being able to pursue my personal work, so I said yes. That was almost nine years ago now, and I’m still as excited about it as I was when I first started.

“I wish I could say that I had a focused, conscientious plan after school…It was simply a series of situations where I found something that interested me and thought, ‘I want to do that next.’”

That’s great. When you were considering whether to go to university or not, did you feel pressured by friends or family to believe that getting a degree was the only way to secure a successful future? I definitely wasn’t the type of person to say, “This is the path I’m taking and you can’t tell me any different!” No way. I was interested in finding the next step to get closer to what I wanted to do. That’s all university ever felt like to me: a step that might enable me to move forward, but not necessarily the step. I didn’t feel that I was cutting off all chances of having a successful career by not getting a diploma. That said, I think my parents would have liked me to go to university, although they weren’t upset or surprised when I told them I wasn’t.

I wish I could say that I had a focused, conscientious plan after school, but I didn’t. It was simply a series of situations where I found something that interested me and thought, “I want to do that next.” It wasn’t until I got older that I started seeing the bigger picture. Today I fully understand my path and where I want to go, and I feel very focused. But at 17 or 18 years old, that was a lot of pressure. Parents and teachers asked, “What are you going to do for the rest of your life?” What a terrifying thing to ask someone at that age! You don’t know who you are at all, let alone who you want to be, and even people at 30, 40, or 50 years old don’t know for sure sometimes.

Pursuing whatever interested me at the time worked for me, but that might not be right for someone else, because they might be more focused. We all have that friend who has known exactly what he or she wanted to do since they were little, but I like to think I’m not alone in being a bit confused and unsure, especially when I was just starting out.

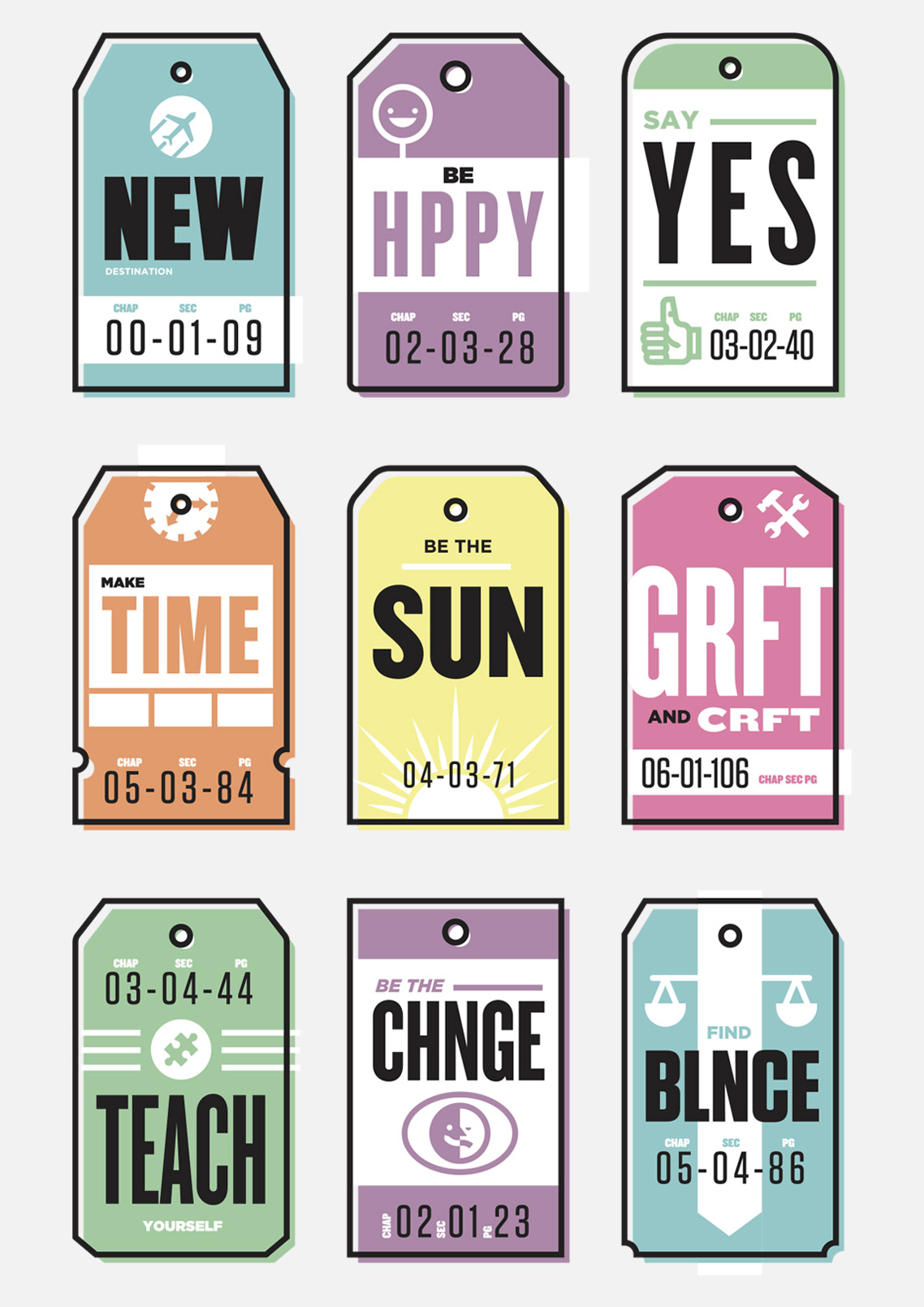

Was that the inspiration behind writing your book, Do Fly? Definitely. There are a lot of people who are interested in many different things and are unsure of what to do, and I don’t want them to feel like they’re failures because of that. It’s okay to be complicated and different. Those types of decisions can take a long time to work out, and people change over time. I want my book to essentially tell people what my parents told me: it’s okay to not know exactly what you want to pursue as long as you pursue something.

When I was writing Do Fly, I didn’t want to prescribe one specific way of doing things, because that’s not how life is. I wanted to give versatile, human advice in a world obsessed with measuring and marking things on a spreadsheet. We can get so focused on stats and numbers, and decisions are made quite coldly that way. I don’t think that’s really how people work, and things can change a lot from one moment to the next. You can’t tell someone, “If you do this, this, and this, then you will have a successful career.”

Young people are constantly pressured to make certain grades or scores in order to feel like they can be successful later in life. Right. That being said, some people greatly excel in that type of system; but many creative people are simply dismissed because they don’t meet that narrow set of standards. They are made to feel like they’ll fail because they don’t fit into a certain box.

Throughout your book, you encourage people to make time for personal projects as a way to help them discover what they might want to do if they don’t already know yet. Yes, one of the great things about doing personal projects is that there is no one to stop you. There is no one to say you can or cannot do something.

The act of making something is not specific to a certain set of people. There are so many people I look up to whose successes feel unattainable. They seem almost god-like because they do and make things constantly while appearing to be untouchable. It can be hard to relate to that, but you need to remember that every single person on the planet has the ability to create.

You also propose something called a “one-nighter” where you ideate, execute, and complete a project in a single night. It sounds like a good way to kickstart the creative process. Definitely. It’s like dipping your toe into something you might not feel comfortable with. It’s good to force yourself into it, because a lot of the time it’s a battle with yourself. Doing personal projects can be especially hard, because people have jobs and spouses and children, so finding time to do something you’re passionate about isn’t easy. I get it: after I come home from work, hang out with my wife, and walk my dog, I can’t get started on personal projects until 9 o’clock at night. I can only work until about midnight or 1am, which is late for me. If you only have a few hours, you have to make them count.

Forcing yourself into a side project is an easy way to see quick results, which is powerful. Once you’ve completed something, even if it’s small, it’s energizing. If you can get feedback quicker by giving yourself a smaller timeframe to complete something, then it becomes a catalyst to go after larger and more extensive projects. It helps you see how far you can push yourself.

“When I was writing Do Fly, I didn’t want to prescribe one specific way of doing things, because that’s not how life is. I wanted to give versatile, human advice in a world obsessed with measuring and marking things on a spreadsheet…You can’t tell someone, ‘If you do this, this, and this, then you will have a successful career.’”

Have you taken any big risks to move forward? I don’t know if I’ve ever taken one big leap. Some people need to make a drastic change in order to feel like they’re progressing, but I generally work from one small, digestible risk to the next. It’s a shame—I almost wish I had lots of massive failures under my belt, but I’m actually quite afraid of being wrong and messing things up. Instead, I use my personal time and projects to try new things and make mistakes and see what might work or not. I essentially do a bunch of one-nighters to quickly iterate and experiment until I feel comfortable.

Some people would consider choosing to go freelance a pretty big risk. What made you feel ready? It was excitement more than anything. Growing up, it didn’t occur to me that I could be my own boss. I didn’t excel at school, and I didn’t feel exceptionally talented. I didn’t think I was good enough, and I didn’t think that sort of thing happened for people like me. The desire to go out on my own was about seeing if I could really make it happen.

You’ve worked as a freelancer and are currently working a creative day job. Are there any insights you’ve gained from your time on both sides of the fence? I’m a big fan of doing both at the same time because you get the best of both worlds. The tricky thing is time management. I like the security of a full-time job. I don’t have to take on project I don’t want because there’s no financial pressure. The projects I take on are for my own creative satisfaction.

You learn a lot as freelancer because every decision and mistake is on you. You’re fully accountable and you understand how difficult it is to find clients, get paid, and put your work out there. You have to do everything yourself, so you appreciate your successes more.

“Growing up, it didn’t occur to me that I could be my own boss. I didn’t excel at school, and I didn’t feel exceptionally talented. I didn’t think I was good enough, and I didn’t think that sort of thing happened for people like me. The desire to go out on my own was about seeing if I could really make it happen.”

What does a typical day look like for you? During the week, I wake up around 7:30 or 8am, shower, and walk my dog. Then I bike to the office and work from 9:30 to 6pm. Throughout the day, I often talk with people in different departments. At lunchtime, I try to work on one of my side projects. I do a lot of different things, but more recently I’ve been on the studio floor surrounded by props, equipment, and cameras.

I go home at 6pm to hang out with my wife, Jane, and cook dinner. She and I spend a half hour or so watching TV or hanging out. Then around 8:30 or 9pm, we clean up and start working on our personal projects. Jane is a freelance jewelry designer, so she often goes to her workshop while I work on whatever side projects I have going on at the time.

Being idle is usually boring to me, but I do try to relax on the weekends. Jane works at a friend’s store on Saturdays, so I hang out and take it easy, but we make sure to spend time together as well. I’ve noticed that balance has been key. I didn’t have that when I was younger—I worked all day and night on Saturday and Sunday, so when Monday came, I was already burned out. I didn’t know when to stop. Now I have a clear distinction between work and play, and I feel very content with it.

What books inspire you? The book that actually inspired me to write Do Fly was Do Purpose: Why brands with a purpose do better and matter more by David Hieatt. I was so excited when I finished reading it.

Another great book is Spark For the Fire: How Youthful Thinking Unlocks Creativity by Ian Wharton. He’s a creative director at AKQA, and I read it cover to cover on the train home from attending his launch party. It’s full of great advice.

I also highly recommend WHY HOW WHAT by the two brothers behind Brosmind. Their work is absolutely beautiful.

I love behind-the-scenes books, like The Art of Dreamworks Kung Fu Panda and The Art of WALL.E—anything that shows a glimpse of what happens during production of a film. One of my favorites is Spike Jonze’s book, Heads On and We Shoot: The Making of Where the Wild Things Are. I am a massive Spike Jonze fan, and the book is an eccentric, sprawling introduction into Spike Jonze’s mind and the crew that he works with.

What movies inspire you? I’m a big fan of documentaries, especially ones about the creative process. One of my favorites is Indie Game: The Movie.

That movie is so good! Can you believe it was their first film? That’s inspirational in itself.

There was a fantastic documentary series called The Run Up: An Artist Documentation Series that was released by Upper Playground years ago on DVD. It profiles artists like Estevan Oriol, Mister Cartoon, and my friend, Mr. Jago. There was another series made ages ago, called Director’s Series, that profiled different film directors like Spike Jonze and Chris Cunningham. I highly recommend that as well.

What music or podcasts do you listen to? The poet and rapper, Scroobius Pip, has a fantastic podcast called Distraction Pieces where he interviews creatives, and it’s really interesting.

I am someone who has to have music on all the time, especially when I’m working. I like a variety: everything from hardcore death metal to instrumental, hip-hop, classical, Frank Sinatra, movie soundtracks, and Taylor Swift—there isn’t much I don’t like.

What type of legacy do you hope to leave? If I could be so bold as to leave one, I hope I leave something people can enjoy and be inspired by after I’m gone. Where the Wild Things Are was made by inspired people: Spike Jonze made that movie after being inspired by Maurice Sendak’s book. The things they made will be remembered and cherished long after they’re gone, and will in turn inspire future creators. I would love it if my work connects with people and inspires them to make something, too.

“I like the security of a full-time job. I don’t have to take on project I don’t want because there’s no financial pressure. The projects I take on are for my own creative satisfaction.”